Uncut

Ultimate Music Guide

|

—

|

Tape recorder on, is it?

Uncut

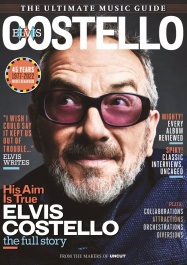

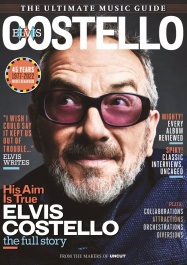

The musical adventures of Elvis Costello: how an angry young man and new wave poet became one of Britain's finest songwriters

|

To the new wavers of 1977, Elvis Costello must have looked a straightforward proposition, a black and white world. Punk's febrile, combative energies and the naïve excitement of golden age rock 'n' roll and mod beat encapsulated in one bespectacled, legs-akimbo, skinny-tied package. And so, for a short while, it would prove; as the arrival of The Attractions — and a pill-popping angry young man attitude — powered Costello on to the new wave front lines with This Year's Model and Armed Forces, his aesthetic cohered around barbed and allusive dissections of pop culture, cutting social commentary and the politics of love and war. A critical darling, and not just because, as Dave Lee Roth bitterly attested, the sleeve of Model was, for most journalists, like looking in a mirror.

In the 148 pages of this Deluxe Ultimate Music Guide, fully updated to account for his most recent activity, you'll read some of Costello's most memorable interactions with just those journalists. Here you'll find spiky moments — "Getting it all down, are you?" — and expansive encounters. Not to mention a full reckoning of the many recordings, collaborations and other adventures which caused them to occur in the first place.

Costello's tale began to twist early on, and never reverted to formula for 40 years. Get Happy!! arrived drenched in classic soul and R&B, looking like it'd been dusted off from the basement of the Twisted Wheel. A country album emerged, Almost Blue, fresh from Nashville itself. A swerve into lush, occasionally baroque art pop for Imperial Bedroom; another into brassy '80s pop for Punch The Clock, home to some of the finest deep cuts in alt.rock history in "The Invisible Man" and "Charm School." The untamed unpredictability of Elvis Costello came to a head in 1986, the year he both premiered the beard on the sleeve of The Costello Show's immaculately authentic country collection King Of America and arguably invented grunge on his unhinged junk rock masterpiece Blood & Chocolate, introducing his Machiavellian alter-ego and ringmaster of the Spinning Songbook tours, Napoleon Dynamite.

Since then there have been Celtic Beard Years, classical quartet collaborations, meetings of minds with the pop, blues and hip-hop greats, torch song collections, experimental electronic endeavours, country and jazz departures and plenty else besides. Costello has evolved from new wave's sharpest rebel poet into a sonic polymath and onstage raconteur, not just one of the country's finest songwriters but amongst its most adventurous too.

Throughout the decades, though, Costello has retained the will and ability to reconnect with that core punk attitude and fire out a firecracker rock record when the mood takes him — a Brutal Youth, a When I Was Cruel, a Momofuku. It's been a skewer holding together a career that might otherwise fly off in a dozen directions, and spears through his most recent run of albums too in the shape of the cranky, incredible The Boy Named If.

An amazing journey for this Jack of all parades, then, and one comprehensively tracked through these pages. We hope you're happy now...

|

This Year's Model

Neil Spencer

"I don't wanna kiss you, I don't wanna touch..." EC lays down the rules of Attractions.

|

Released just eight months after his debut, This Year's Model proclaimed an altogether different pop animal to the geeky songwriter of My Aim Is True. Its cover portrayed Costello not as oddball wannabe but as young meteor, poised behind a Hasselblad camera, pulling the strings, in control. The music had taken on an equally dramatic shift with the recruitment of The Attractions, whose well-schooled talents had slotted together cannily during 1977's frenetic gigging. In the studio, with producer Nick Lowe on inspired form, the quartet emerged with a record that sounded like no-one else, a masterpiece that alchemised Costello from aspiring songwriter to fully formed creator. Hereafter he was a player.

The change was not altogether unexpected. "Watching The Detectives" had already crashed the charts, and though Costello was not himself punk, the anger, confrontation and self-lacerating honesty of his songs, together with the absolute fury of his live shows, slotted sweetly into the mayhem of 1977. On or offstage, there was no spikier presence in town.

Few, however, had anticipated an album as startling and focused as This Year's Model. Sonically, it was utterly distinct. Whatever its sentiments, the punk revolution was founded on guitar rock, and while Costello's Fender is a driving presence here (see the opening splash of power chords on "No Action"), the album is defined by the insinuating whine of Steve Nieve's Vox Continental — an instrument wildly out of favour since its 1960s heyday — and by the booming precision of a rhythm section that Lowe made the centrepiece of his mix. The results could be Spectoresque in their onslaught ("Pump It Up"), slide into jangle pop ("Lip Service") or turn mysterioso psych with a flick of Nieve's keys. At the record's heart was Costello himself, unleashing a torrent of acidic wordplay on a dozen songs that were each distinct but whose sprays of imagery bled into each other. Thematically, This Year's Model is virtually a concept album, summed up by two words: woman trouble.

And what trouble. The sneered opening lines — "I don't wanna kiss you, I don't wanna touch" — were the antithesis of gooey pop tradition, though elsewhere Costello mutated from anti-romantic ("I don't want anybody saying you belong to me") to embittered loser ("Knowing you're with him is driving me crazy"), sinister stalker ("I'll be at the video and I will be watching") and passionate suitor ("It's you, not just another mouth in the lipstick vogue"). Emotionally, This Year's Model's withering put-downs and proclamations of passion make for a contradictory but electrifying ride through modern romance. Presciently, telephones play a big part in the narrative, with Costello either waiting on a call or ranting down a mouthpiece while claiming that he's "not a telephone junkie."

Curiously, for an album that screamed modernity (Barney Bubbles' graphics emphasised the point), This Year's Model has a strong 1960s streak. While its deliberately miscropped cover evoked David Bailey (and David Hemmings in Blow-Up), the gangster persona of "Hand In Hand" is pure Kray Twin (and Harry Flowers in Performance). Its Vogue cover models and the Chelsea Costello has no desire to visit belong not to King's Road 1977, but to the chi-chi West London of a previous era. For most pop writers, the catwalk had long since ceased to hold any fascination; despite the protests that "you don't really give a damn about this year's girl," Elvis seemed fixated, "Out in the fashion show / Down in the bargain bin."

"I Don't Want To Go To Chelsea" is one of several stand-outs, a snarl against empty-headed glamour built on an itchy reggae riff from Costello's guitar, though Costello has mused that he was also trying to rewrite The Kinks' "All Day And All Of The Night." Reggae was everywhere in 1978, and Costello had already used a laid-back rhythm for "Detectives" (and, clunkily, for "Less Than Zero"), but on This Year's Model reggae's influence is subtler, yet pervasive. The drop-outs of "This Year's Girl," the opening riffs of "The Beat" and "Living In Paradise" and the neo-dub of "Chelsea" all owe a debt to Jamaica. The switch from edgy reggae to cavernous pop is constant, whether in a single song ("The Beat") or in the gear change between, say, "Paradise" and the high-tempo rock of "Lipstick Vogue."

The clever architecture of the songs, their dramatic key shifts into bridges, middle eights and choruses, called for a musicianly acumen beyond most emergent acts, but The Attractions never faltered (the singing bassline of "Lip Service," for example, remains worthy of McCartney). Nick Lowe's production likewise doesn't miss a trick — the backward tape that opens Side Two with "Hand In Hand" adds a touch of psych menace, the handclaps that punctuate "Lip Service" give a nod to '60s pop — though Basher also knows when to sit back and let the band rip on "Pump It Up," whose breathless, accusatory vocals bear a hint of Dylan's "Subterranean Homesick Blues."

The glum "Night Rally" doesn't seem to have much to do with the rest of This Year's Model, a musical plod at variance with the melodic cavalcade elsewhere. At the time, though, with the National Front a presence on the streets, its anti-fascist imagery carried an urgency that finds an echo today, as do images of "the corporation logo flashing on and off in the sky." A necessary piece of ballast.

Beyond its exhilarating musicianship, what do the lyrical flourishes of This Year's Model amount to beyond a man deep in the most troubled kind of love, one that's "just a tumour, you gotta cut it out"? ("I wished he liked girls more," remarked critic Robert Christgau).

Part of the album's appeal was and is that its songs apply ruthless authenticity, one of the battle cries of the punk insurrection, to personal relationships. So jealousy, betrayal, longing, repulsion, self-hatred, vengeance — bring 'em on. It's about being real, instead of "just going through the motions," about wanting something deeper than "those disco synthesisers" or the phoney world of the latest celebrity pin-up. In modern times, This Year's Model still chimes perfectly.

|

|

Get Happy!!

Jim Wirth

Hi, fidelity? Why EC's frantic tribute to Motown and Stax is no laughing matter.

|

"He drinks in self defence," Elvis Costello sings on "Temptation," a fair indication of the point his life had reached in the months leading up to Get Happy!!. Recorded in October 1979, Costello's uneasily cheery pastiche of Motown and Stax has a lighter tone than its immediate predecessors, with the quirky sleeve's integral ringwear designed to make the package seem like some well-thumbed 1965 Tamla release. However, it is all a cosy blanket covering an uneasy, and occasionally dissolute mess, smart lines sparkling in deep and muddy emotional waters.

"Dying to be so bad is bad enough," sings Costello, voice worn ragged on Get Happy's wearily defiant closer, "Riot Act." "Don't make me laugh by talking tough." Costello's attempts at acting the big man, of course, had led to substantial problems. Goaded to no small extent by tough-guy manager Jake Riviera, who had actively encouraged the siege atmosphere that surrounded the singer as he broke America, Costello was reluctant to be an easy commodity. As he had growled on stand-alone 1978 single "Radio, Radio," a hate-letter to the music business: "I wanna bite the hand that feeds me / I wanna bite that hand so badly."

He duly bit off substantially more than he could chew after a show in Columbus, Ohio on March 15, 1979, a drunken spat with members of Stephen Stills' entourage — and particularly Bonnie Bramlett, once of Delaney & Bonnie fame — descended into a fight.

Beset with death threats and a radio black-out, Costello showed contrition at a New York press conference on March 30, 1979. "Nobody said that to make records you've got to have a certificate that says you're a nice and wonderful person," he said, struggling to maintain some dignity. He has been apologising ever since. This in 1982: "I said the most outrageous thing I could possibly say to [the Stills party] — that I knew, in my drunken logic, would anger them more than anything else." Then a lifetime later in 2010: "I thought [I] was being ironic," and again, "Despite everything else that I've stood for, that's still mentioned."

Many read the affection for soul music expressed on Get Happy!! as a musical act of penitence, but the lessons in humility are seemingly more to do with his well-publicised dalliance with November 1974 Playmate Of The Month Bebe Buell, and the uneasy reconciliation with first wife Mary Burgoyne. A 25-year-old father and husband, Costello's discovery — expressed on unflattering third-person pen pic "The Imposter" — that he is "not the man you think that he could be" is everywhere. A sense of inadequacy underpins Get Happy!!, along with the feeling that he has simultaneously underpaid for and been short-changed by love.

Opening pun fiesta "Love For Tender" sullies human emotion with the language of high finance, and finds Costello very much in arrears: "You can total up the balance sheet, and never know if I'm a counterfeit," he sings over a chirpy, finger-clicking backdrop. His fakery is further exposed on the uptempo "The Imposter," the protagonist "Dying to be too bad, trying to talk too tough, trying to jack the lad." Trying, and notably failing.

Bewitched and utterly bewildered by the "double duchess" he encounters in "New Amsterdam," Costello finds his career capital also loses a lot on the foreign exchanges. "Back in London they'll take you to heart after a while," he muses. "Though I look right at home, I still feel like an exile."

In a world — or indeed a continent — where insincere compliments are seemingly easy to come by, Get Happy!! plunges Costello into a quest for something like truth. "Everything you say now sounds like it was ghost-written," he wonders in horror of his paramour on "New Amsterdam." While his idiot "King Horse" alter ego is besotted with the trappings of success ("So fond of the fabric / So fond of fabrication"), the newly wise Costello suddenly sees deception everywhere. "Her bedroom eyes were like a button she was pushing," he notes of one bedfellow on "Opportunity," while seeing sex through a one-night stand's eyes on "Motel Matches": "Though your mind is full of love, in your eyes there is a vacancy."

Inauthentic love is bad enough, but authentic lovelessness is no better. On "Possession," Costello paints a joyless picture of a decaying cupboard-love relationship, seemingly culminating in a last night at home before heading out on tour: "So I see us lying back to back, my case is closed, my case is packed / I'll get out before the violence, or the tears, or the silence."

Extra-marital sex, though, does little to warm a cold heart. His voice utterly ravaged on the bed-hopping "High Fidelity" (or should that be 'Hi, Fidelity'?), Costello expresses some hollow-eyed sense of adulterer's remorse ("Maybe I got above my station, Maybe you're only changing channels"), but a more selfish disappointment with the essential architecture of romantic relationships is the overriding emotion on Get Happy!!. It's all compromised. None of it works. "Everybody's hiding under covers," Costello wails as he looks to wipe the slate clean on the under-eulogised "Clowntime Is Over." "Who's making Lovers' Lane safe again for lovers?"

Costello unburdens himself of an intercontinental flight's worth of emotional baggage on Get Happy!!, but — with 10 songs a side on the original version — fast scene changes cover up for any sameyness in the action, with some unbelievably good material flashing in and out of focus at high speed (the enigmatic "Secondary Modern" is a less-noted career highlight).

It is the album where he abandoned any remaining pretence of being in the musical vanguard, perhaps, but as his "post-punk Bob Dylan" bubble burst ignominiously, Get Happy!! might be the first record where Costello dared to show some vulnerability. No longer so big or so clever, Costello's usual wisecracking fury takes a stylish turn towards a more modest sense of self-awareness. Not necessarily authentic soul music, but music with a genuine soul.

|

|

Almost Blue

Rob Hughes

"WARNING: This album contains country & western music and may cause offence to narrow-minded listeners."

|

If Elvis Costello had been toying with the idea of retiring from music prior to Trust, its disappointing sales numbers hardly lightened the mood. His marriage was failing, he was drinking too much, and the collective tension within The Attractions showed little sign of easing up.

As a consequence, he chose to take a break from songwriting altogether — though crucially, not from the studio itself. Costello had come to the conclusion that he could better articulate his current state through other people's songs. And what better medium to express his sorry disillusionment than country music?

This was no arbitrary solution to a dilemma. Costello had been a country disciple for most of his life. Hank Williams was part of the repertoire during his folk club days as Declan MacManus, and during the Live Stiffs jaunt of '77, it was suggested that he remove The Best Of George Jones from the tour bus for fear of "confusing" guests from the music press. The same rationale, you suspect, was behind the label's decision to nix the Jones-apeing "Stranger In The House" from My Aim Is True. Costello had eventually realised an ambition, though, when he and Gorgeous George cut a duet of the song for the latter's My Very Special Guests in 1979.

Seduced by the self-destructive tropes of classic country, Costello opted to go the full mile on his next album. He and The Attractions flew to Nashville and hired Billy Sherrill, famous for his work with Jones, Tammy Wynette and Charlie Rich, as producer. Also in tow was a camera crew from The South Bank Show, their interest piqued by the sight of one of Britain's edgier talents making a detour into the distinctly unhip realm of country.

The band were joined by fiddler Tommy Millar and lead guitarist/pedal steel player John McFee at CBS' Studio A, where Costello had shortlisted a bunch of songs previously recorded by the likes of Hank Williams, Patsy Cline, George Jones and Gram Parsons. The latter was a key signpost on what became Almost Blue. Costello's initial interest in country had been sparked by the discovery of two Parsons-heavy albums as a teenager: The Byrds' Sweetheart Of The Rodeo and The Flying Burrito Brothers' The Gilded Palace Of Sin. Both records ached with a peculiar sense of longing, made all the more potent by a soulful voice that seemed to foretell some hopelessly broken future.

Given that Parsons died young, at just 26, the sentiment of these songs now drew Costello in deeper. Two Gram covers made it onto Almost Blue. The first, "I'm Your Toy" (aka "Hot Burrito #1"), found Elvis in potent form, crying hurt while his onetime lover sinks into the arms of another. It's a midtempo ballad that more or less sticks to the arrangement of the original, as does the second Parsons co-write, "How Much I Lied," marked by Steve Nieve's rolling piano riff.

Such faithful adherence to source material was a constant puzzle to Sherrill. This clearly wasn't what he was expecting. And while Elvis fans no doubt had similar concerns about the choice of producer (as a pioneer of Nashville's countrypolitan sound, Sherrill was noted for sugaring his work with liberal use of strings), Costello knew what he was aiming for. If the choice of song was right, he argued, there could be a genuine tension between the emotion of the singer and Sherrill's smooth backdrops.

Yet Sherrill couldn't understand why an English ex-punk would want to cut an album of "worn-out" country covers. His barely disguised indifference to the whole thing caused a degree of tension in its own right. Only when Costello and the band ripped through an utterly irreverent version of Hank Williams' "Why Don't You Love Me (Like You Used To Do)?" did the producer get animated at all, double tracking the song for added oomph. Most of the time, though, as Costello recalled later, "it was less of a collaboration and more of a contest in cultural differences." He added: "Anybody who has seen The South Bank Show will know Mr Sherrill as an impatient man with an overwhelming interest in speedboats."

Still, over the course of 12 days in Nashville, the band recorded over 25 covers, of which a dozen made it onto the album. It was only fitting that, given Costello's predilection for booze, a pair of drinking songs made the final cut. One of them is an uptempo take on Merle Haggard's "Tonight The Bottle Let Me Down," imbuing the song with a fine dash of R'n'B swing. The other is Charlie Rich's gin-soaked "Sittin' And Thinkin'," which proved a capable vehicle for both Sherrill's backing choir, Nashville Edition, and the weepy drift of McFee's pedal steel.

As if to pre-empt a tough reception, at a time when populist country in the UK meant little more than Kenny Rogers and Crystal Gayle, Almost Blue's cover came with a sardonic sticker: "WARNING: This album contains country & western music and may cause offence to narrow-minded listeners." It fared better than Costello may have expected, however, outselling Trust and landing him a first Top 10 hit for 18 months with "A Good Year For The Roses." Written by Jerry Chesnut and originally cut by George Jones, it's a classic break-up ballad that Costello tackles admirably.

Almost Blue certainly isn't perfect, but neither is it the ill-judged genre exercise that some critics, especially in the US, tried to make out. Some reviews were scathing. The Washington Post declared it "a mean-spirited mess," while Creem dismissed Costello as little more than a "hack lounge singer." Elvis countered by suggesting that Americans resented him for daring to play their music.

At the surface, Almost Blue is simply a case of one man tipping the wink to the songs and artists who moved him. But the album also served to resolve something of a crisis of faith in his own songwriting ability, allowing Costello to clear the ground for his next endeavour, the wholly different Imperial Bedroom.

|

|

Punch The Clock

Peter Watts

A technical knockout of '80s pop. And, behind the horn section, lurk two political classics.

|

You can probably get a handle on Elvis Costello's feelings for Punch The Clock by the fact that, when asked to write sleevenotes for a 2003 re-release, he claimed to be "unable to recall a single further entertaining incident that occurred during these sessions," so simply reprinted the essay that prefaced the 1995 reissue, complete with typing errors. Punch The Clock is an awkward entry in Costello's catalogue. Boasting an atmosphere of superficial jollity, but also two of his finest, most deeply felt, political songs, it's an album that has to be considered a success on its own terms. It's the nature of those terms that left the strange taste in his mouth.

In 1983, Costello needed a hit, to get "reacquainted with the wonderful world of pop music." As he admitted, "If you allow contact with the mainstream audience to be severed for too long, you lose the freedom to do what you want to do." America hadn't shown much interest in Almost Blue or Imperial Bedroom, and the UK Top 30 hadn't been troubled since "Good Year For The Roses," so Punch The Clock has purpose and begins with gusto. "Let Them All Talk" and "Everyday I Write The Book" are frantic, full and ridiculously charming: the former is packed with crusading, peppy horns, the latter led off by a modern approximation of Motown backing harmonies. Slick, synthetic but by no means unpalatable, this was Costello embracing what he called the "passionless fads of that charmless time: the early '80s."

To his credit, it was a challenge Costello took seriously. First, he recruited the best pop producers in the land, Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley, who had married commercial success with artistic credibility on a succession of great singles with Madness, Teardrop Explodes and Dexys Midnight Runners and who brought with them the TKO Horns section. Costello wrote songs with the horns in mind, and when Langer asked him to stop his bedroom moping and write something with zest, Costello obliged, picking up the guitar for a sequence of songs about love and marriage. The first of these was "Let Them All Talk," which begins the album with a bounce that requires Costello produce a superb vocal performance to keep up, delivering a wry lyric that comments on "the sad songs that the radio plays."

It's followed by "Everyday I Write The Book," conceived by Costello as a Merseybeat spoof but successfully redrafted in the studio with a Motown feel. Backing vocals came from Claudia Fontaine and Caron Wheeler, known as Afrodiziak (Wheeler later sang Soul II Soul's "Back To Life"). The song exemplified the Langer/Winstanley process, patiently rebuilding a song track by track, using little of the original and demanding numerous retakes. It was a laborious process that didn't sit naturally with the spontaneity of The Attractions, but when it worked, the results were splendid. The excellent "Everyday I Write The Book" was, confessed Costello, "one of our very few entirely cheerful recordings." It reached No 33 in America, his first US hit.

Two songs in, and while Costello had made his point, he'd also set a pace impossible to maintain. The throwaway "The Greatest Thing," written to Langer's orders, is a "proud and wishful song on love and marriage" in which Costello rarely sounds as if he means what he's singing. It's followed by the woozy whimsy of "The Element Within Her" and "Love Went Mad," the latter an insubstantial hotchpotch that conceals a couple of arch lines ("a self made mug is hard to break") amid careering inanity.

Just when a trend seems to be established — undercooked songs meets overbaked production — Punch The Clock hits you with not just the best song on the album, but one of the best songs Costello has written. "Shipbuilding" started with a piano melody written by Clive Langer. Asked to supply lyrics, Costello went on tour in Australia, where he followed the Falklands war between Argentina and Britain through the tabloids, and produced a stunning, sad but above all wise meditation about war, industry, economy and class. Released as a single with Robert Wyatt supplying elegiac vocals, "Shipbuilding" had been a minor hit in April 1983, but Costello always planned to do his own version and, to distinguish it from Wyatt's version, called in Chet Baker to contribute mournful trumpet. Wynton Marsalis and Miles Davis were also considered, but Baker's solo is magnificent, even if he was "pretty spaced out" according to Langer, who pieced it together from three takes.

Side two kicks leads off with the horn-happy "TKO (Boxing Day)," with Costello ungallantly noting that "Now you don't look so glamorous, whenever I feel so amorous" and offering a bewildering litany of puns: "They put the numb into number, put the cut into cutie/ They put the slum into slumber and the boot into beauty." The tempo is sustained on the light funk "Charm School," with Afrodiziak contributing some of their best backing vocals, before "The Invisible Man," pulled together from discarded lyrics, struts into view like a Kinks outtake. The sequence of "Mouth Almighty" and "King Of Thieves" offer a low point, the former a half-hearted pop ballad, the second sprawling and shapeless. Given that the equally modest Squeeze-lite "The World And His Wife" is yet to come, the only thing saving the second half of the record from complete mediocrity is a song that, like "Shipbuilding," Costello didn't even write for the album. "Pills And Soap" was based on Grandmaster Flash's "The Message," with Costello delivering a tremendously cynical lyric, ostensibly about the iniquity of the tabloid press but also about political deceit and establishment hypocrisy, over a drum machine and Steve Nieve's dramatic piano. Stark and demanding, it came out before the general election of May 1983, with Costello styling himself The Imposter. He planned to bring it out on red vinyl in the event of Labour victory but, denied that satisfaction, instead covered The Beat's anti-Thatcher "Stand Down Margaret" on the BBC. Shortly after, Punch The Clock was released to a receptive public. Costello's calculated gamble had paid off, but it was a tightrope act he'd struggle to repeat.

|

|

King Of America

Andrew Mueller

Introducing The Costello Show, The Little Hands Of Concrete, and an illustrious new supporting cast... Declan MacManus' crowning glory?

|

We've become accustomed, 37 years into his career, to Elvis Costello's unpredictable waxes and wanes. However, around the time of the release of his 10th album, King Of America, there was considerable muttering to the effect that Costello was no sure long-term proposition. He had gone up like a rocket, this argument went, releasing five nigh-flawless albums in as many years straight off the launchpad, and had since been wafting slowly back down through less rarefied stratospheres, via a country covers project, a somewhat overheated orchestral pop opus, a Philly soul digression and, most latterly, the muddled, portentously titled Goodbye Cruel World. When he broke what was, by his standards, an epochal silence of two years with a hoarse, desperate swipe at The Animals' "Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood," many assumed that Elvis had, to all intents and purposes, left the building.

The outward appearance of King Of America offered little reassurance. The LP was formally credited, somewhat bafflingly, to The Costello Show (one of few places his familiar pseudonym appeared at all, with songs credited to Costello's real name, Declan MacManus, and guitars to The Little Hands Of Concrete, owing to a predilection for in-studio string-breaking). The cover was a sepia headshot of Costello sporting a beard, brocaded jacket, crown, and expression of bored insouciance, of the sort that might well preface inquiring, of some simpering serf, "And what is it that you do?" The sleevenotes prompted further bewilderment. It was surprising enough that The Attractions appeared on only one track, rather more so that for much of the album Costello was backed by men who had, until a decade previously, been playing for another Elvis: the TCB Band themselves, James Burton, Jerry Scheff and Ron Tutt. Also aboard were supreme jazz bassist (and once Mr Ella Fitzgerald) Ray Brown, former Little Richard (and almost everybody else) drummer Earl Palmer, and such top-drawer sessioneers as T-Bone Wolk, Mitchell Froom and Jim Keltner. If Costello had submitted to hubris, he hadn't done it by halves.

In his disarmingly candid essay accompanying the 1995 Demon reissue, Costello explained himself. "Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood" had been Columbia's choice of single, rather than his. The sidelining of The Attractions had been semi-accidental. An original plan to have them play on half the album had been overtaken by the fact that by the time they arrived in LA, sessions had gone so swimmingly that more than half was already done — leaving, as Costello recalled, "my sullen and estranged band hanging around our hotel harbouring a grudge or honing an embittered anecdote" (a good few of the latter, barely fictionalised, would surface a few years later in Bruce Thomas' score-settling memoir, The Big Wheel). It was hopefully some consolation that the one song The Attractions did play on, "Suit Of Lights," was very arguably the best thing on what was clearly, once you got around to playing the damn thing, one of Costello's very finest records.

Costello, steeped in a learned love of Americana, was always going to make a country record — his own country record, that is (Almost Blue, the respectful covers album recorded in Nashville with Billy Sherrill a few years earlier, felt in retrospect like EC's establishment of his credentials in this department). But throughout King Of America, Costello is both too smart and too confident to adapt himself to country tropes — that way, he knows, lies fatuous imposture, empty pastiche and the rarely edifying spectacle of Englishmen wearing cowboy boots. Instead, he adapts country to Elvis Costello — and country responds enthusiastically, as a genre always sympathetic to unusual voices and cunning lyricism would. Any doubts that he'd struck the right note were vanquished within the year when a reading of the rueful hangover romp "The Big Light" appeared as the opening track on Johnny Cash's Johnny Cash Is Coming To Town (other King Of America tracks to have been adopted by American country singers include Laura Cantrell's "Indoor Fireworks" and Rhett Miller's "Brilliant Mistake," and while it remains an outrage that George Jones never recorded "Our Little Angel," Rosanne Cash did).

Crucially, for all that he is recording in some of America's best-known studios with some of America's best-regarded musicians, Costello never loses sight of the fact that he's a stranger here — the opening lines of opening track "Brilliant Mistake" sound, in context, like a caution against succumbing to these kind of assumptions ("He thought he was the king of America / Where they pour Coca-Cola just like vintage wine"). On the heavily Cash-influenced "Glitter Gulch," he's the aghast, seduced hotel-room-flickerer between gaudy game shows on US television, underpinned by a James Burton masterclass on guitar and dobro. On the gentle waltz "American Without Tears" — a true story, by Costello's account — he sees something of himself in two elderly English GI brides drinking in a hotel bar, who don't quite belong here but can never really go home (a sequel, "American Without Tears No. 2," can be found on the Out Of Our Idiot compilation).

For all its explicit rooting in foreign soil, King Of America peaks at the points at which Costello is at his most personal — and therefore his most universal. "I'll Wear It Proudly" and its companion piece "Jack Of All Parades" are two of his most poised love songs, the former a beautiful devotional leavened with grateful humility ("In shameless moments / You made more of me than just a mess"), the latter an acknowledgement of the terror of losing something you never expected to have ("When we first met I didn't know what to do / My old love lines were all worn out on you"). The presumable subject of this pair, former Pogues bass player and soon-to-be Mrs Costello Cait O'Riordan, is also credited with co-writing the winning rockabilly shuffle "Lovable."

King Of America isn't perfect. At 15 tracks, it may be too much of a good thing — it could have lived without the rehearsal-room workout of J.B. Lenoir's "Eisenhower Blues" and the oversold ballad "Poisoned Rose." But it's a great record in its own right, and an important one, for better and for worse, in confirming to Costello that there might be life beyond The Attractions — after, that is, he'd put the old gang back together for one more job...

|

|

Spike

Neil Spencer

Irish folk? New Orleans funk? Americana? A Costello/ McCartney dream team? The Beloved Entertainer stretches out...

|

As the 1980s dwindled, Elvis Costello found himself in the unusual position of not knowing what to do next. Amid a host of plans and projects, which was the one to pursue? By the end of 1987, his protracted break-up with The Attractions was (more or less) completed, while he had slotted in international dates with The Confederates. His marriage to Cait O'Riordan was still in its honeymoon and Costello was much in the orbit of The Pogues, with whom O'Riordan played bass. Further, he had been working with Paul McCartney, who had proposed the pair write an album together. By the start of 1988, he was also penning the soundtrack for The Courier, an Irish film that featured O'Riordan in its cast.

Costello was in truth all over the place, his restlessness and dissatisfaction with his career arc reflected in the welter of soubriquets he had adopted over the previous couple of years, and in his ceaseless changes of musical approach. Was this desperation in the guise of a questing spirit, or simply a loss of direction?

Both, actually. As he considered his first album for a new label, Warners, Costello's head swam with ideas. Apparently convinced that any genre was his for the taking, he envisaged a series of four, even five albums. There would be another Americana record with Coward Brother T Bone Burnett, a venture into New Orleans territory with some of the Crescent City's finest, yet another using the Irish folk flavours he enjoyed with The Pogues, and then a more mainstream pop album, possibly the McCartney project...

What emerged from these grand visions was Spike, a diffuse sprawl across genres, a fascinating and sometimes inspired collection that refused to become more than the sum of its parts. Its uncertainty is there in a cover shot of Costello in clown greasepaint — or is it music hall demon? — with "The Beloved Entertainer" inscribed below, yet another toyed-with alias, as if any but the most ardent Ellophile cared what nom de plume was currently in favour. It was all Costello, after all.

Not quite. Spike was the first Costello album with co-composer credits — a brace with McCartney, another with O'Riordan. It also boasts a giddy array of guests clustered around each of its several recording locations. The aristocracy of Irish folk graced the Dublin sessions — Dónal Lunny, Davy Spillane, Christy Moore. The LA studios drew Roger McGuinn, Mitchell Froom, Marc Ribot, Jim Keltner, with co-producer T Bone Burnett also lending a hand. New Orleans provided The Dirty Dozen Brass Band under the supervision of soul maestro Allen Toussaint. Back home there was a near-duet to be sung with Chrissie Hynde, and of course, somewhere, Nick Lowe was on bass. The sessions were a logistical jigsaw, with parts recorded in one city and augmented elsewhere. But if scattered, Spike was also fearless, Costello putting himself among the top brass of his profession.

Could he rise to the various occasions? Mostly. Opener "This Town" unrolls grandly with a chiming chorus of "You're nobody in this town until you're a bastard," with intriguing vignettes of modern-day bastardry in its verses. "Deep Dark Truthful Mirror," a potentially awkward mid-tempo piece of finger-pointing, is lent gravitas by Toussaint's rippling piano and the growls of the Dirty Dozen Brass. There's a wry joy to the cabaret of "Miss Macbeth," with its Beatlesesque Wurlitzer, while the actual Beatle presence delivers a highlight — and much-needed hit single — in "Veronica." Costello provided the song, about an old lady drifting into absent-mindedness, more or less intact, but Macca's added chorus swirls the song upwards into exuberance. The pair's other co-write, "Pads, Paws And Claws," is a less fortunate affair, a nondescript neo-rockabilly that never gets past its title.

Best of all comes "Tramp The Dirt Down," an elegant excursion into Irish balladry, simply and sweetly played by the doyens of the craft, cradling one of Costello's most vitriolic tirades, aimed not at a lover but at Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Costello's revulsion at the sight of the baby-kissing Iron Lady triggered the song, which contrasts her smiles with the miseries inflicted by her policies: "I never thought that human life could be so cheap." Reflecting a widespread loathing for her regime, its sentiments are delivered drily, or at least as dry as hoping to stamp on someone's grave can get. Only towards the end does Costello's voice crack with bile. Heaven knows what the world made of it, but in Eire and Albion the cheers rang. True to his word, Costello continued to sing the number after Thatcher's death in 2013.

"Any King's Shilling" allows the Celtic contingent more space to stretch out musically, and they produce a majestic arrangement for one of Costello's most impassioned vocals, cautioning a young man against "putting your silly head in that British soldier's hat"; it could as easily belong to the "troubles" of the 1920s as the 1980s.

Yet for every triumph on Spike there is a so-so counterweight. "Chewing Gum" is a stab at funk that's too strong for Costello's reedy vocals. "Satellite," with Chrissie Hynde backing, struggles to establish a clear identity. "Last Boat Leaving," written for The Courier, is a pleasant plod. "Let Him Dangle," about the last man to be hanged in Britain, is a well-meant polemic against the death penalty but one that, chorus aside, comes melody-free. "God's Comic," cut from the same cloth as Randy Newman's "God's Song," has some droll lines — EC imagines The Almighty listening to Lloyd Webber's Requiem and remarking "I preferred the one about my Son" — but its conceit and mock jaunty arrangement soon outwear their novelty.

Then there's "Stalin Malone," a beautifully played instrumental from The Dirty Dozen Brass, intricate yet catchy. Costello seems to have realised that fitting in an equally elaborate set of lyrics — sample: "the jazz band drowns out the hysterical bird" — would be inviting trouble, so the track stays gamely but oddly a stand-alone. One might say the same

of Spike as a whole; among Costello's huge output it's a one-off in its diversity, and if its contents don't quite coalesce, its stand-outs and bravery still shine.

|

|

The Juliet Letters

Andrew Mueller

Rock 'n' roll, where art thou? A confounding, undervalued hook-up with The Brodsky Quartet.

|

"This is no more my stab at classical music than it is the Brodsky Quartet's first rock and roll album," declared Elvis Costello in the (extensive) sleevenotes of the original release of The Juliet Letters. A measure of defensiveness was understandable. As Costello had learned the hard way, over 13 previous albums of restless reinvention and innovation, and the often bewildered and/or outraged response to same, rock fans — for all their rebel posturing — are often extremely conservative and possessive people.

There was indeed reason to fear that those who would have preferred he never outgrew the sweaty, splenetic, knock-kneed, misanthropic punk rocker on the cover of My Aim Is True and This Year's Model might be other than welcoming of what was — and there was really no getting around this — an emotionally complex concept album made in cahoots with serious string players. Or, as a senior figure at one music weekly remarked when the first violin trills of the brief instrumental fanfare "Deliver Us" were broadcast across the office, "Has the King of Albania died or something?"

The suspicions engendered by The Juliet Letters were mostly to the effect that Costello was being deliberately and obtusely whimsical and/or insane and vainglorious and/or was making a clumsy and faintly pitiable attempt to be taken seriously. The last of these was convincingly debunked by Costello himself in the (even more extensive) sleevenotes of the 2006 reissue of The Juliet Letters ("Clearly, anyone who made such a statement had little or no knowledge of critical hyperbole that can rain down on even the slightest talent before the bloom goes off the romance in pop music. I had found myself being taken too seriously and over-analysed from the very outset of my recording career.") The other accusations were rather more a reflection on those making them than the object of them: imagination and ambition seem strange insults to level at any artist, or indeed anyone.

The more prosaic truth of the gestation of The Juliet Letters was that Costello had chanced across a newspaper article about a Veronese professor who had taken to replying to the correspondence the city apparently received addressed to Juliet Capulet. Costello, not unreasonably, was intrigued by the idea of what people might be writing to a fictional or at any rate long-dead character, and what one could possibly say in reply. At around the same time, he was entranced by The Brodsky Quartet's performances of Shostakovich's string quartets at Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, and over the next few years became a regular at their concerts — unaware, as he tells it, that the Brodskys had also been to see him play more than once. They began discussing working together in 1991, and The Juliet Letters was premiered in London and Dartington in the summer of 1992, after which the album was recorded, live in the studio.

The Juliet Letters is a punctiliously equal collaboration: Costello contributes to the music, the Brodskys to the words. For all that, The Juliet Letters, like few other Costello albums before or since — North is perhaps the only comparison — is dominated by Costello's singing voice. This is understandable — he'd cut that unmistakable serrated whine to be heard against vastly more clamorous backing. And it's mostly no problem at all, at least for listeners who have acquired what remains a divisive taste. His impersonation of a vindictive grandmother plotting disinheritance on "I Almost Had A Weakness" owes much to such previous sanctimoniously enraged outbursts as "Blue Chair" and "How To Be Dumb"; "This Sad Burlesque" is a descendant of such beard-era baroque triumphs as "All Grown Up" and "God's Comic," and his ominous muttering of "For Other Eyes" recalls "Pills And Soap" (a Brodskyfied version of which would form part of the encore at live performances of The Juliet Letters).

But the worst and best moments of The Juliet Letters are those at which Costello tries to find new voices for this new context. On "Swine," he affects a nasal, declamatory bark to suit a screed of deranged ranting ("You're a swine and I'm saying that's an insult to the pig"), but sounds perhaps too convincingly like a ragged-trousered itinerant barking at traffic outside an off-licence. Similarly, the hoarse barrow-boy yelp of "This Offer Is Unrepeatable" suits the chain-letter huckster narrating the lyric, but entices the repeat listener as little as spam of this sort ("Ignore at your peril this splendid advice") entices sane recipients. On a few other tracks, especially "Romeo's Seance" and "The First To Leave," Costello could perhaps have afforded to rein in his sometimes hyperactively tremulous vibrato just a little.

But when he properly hits it, he's magnificent. The creeping, obsessive "Taking My Life In Your Hands," the glorious show-stopper that heralded the intermission in live performances of The Juliet Letters, builds slowly and sumptuously to a crescendo that Costello surely has no hope of reaching, until he does, at which he suddenly resembles some seething, vindictive cousin of Bobby Hatfield (a compliment, in these circumstances).

The Brodsky Quartet are predictably extraordinary throughout, as capable of the stately and restrained ("The Letter Home," "This Sad Burlesque") as they are of the playful and poppy. "Jacksons, Monk And Rowe," for all that it was mostly written by the Brodskys' Michael and Jacqueline Thomas, would have fitted seamlessly onto one of Costello's more arranged albums — Imperial Bedroom, say, or Spike. It says much about the seamlessness of Costello's association with The Brodsky Quartet that it barely seemed remarkable when they did pop up on a couple of his subsequent albums, playing on a track each of All This Useless Beauty and North, or when Costello appeared on their Moodswings.

No Elvis Costello album has been so witheringly pre-judged as The Juliet Letters. It may be for that reason that it rarely features among lists of his best works. Indeed, it must be that, because there's not a lot wrong with the songs.

|

|

Kojak Variety

Garry Mulholland

Hidden charms! Mercifully rescued from the archives: a crate-digging covers set recorded on an all-star jaunt to Barbados.

|

A for a celebrated songwriter, Elvis Costello has recorded and performed an awful lot of covers. Kojak Variety might stand as only his second, and thus far final, album of cover versions, but by 1995 Costello had released over 40 interpretations of other songwriters' material, and the 2004 remastered edition of Kojak Variety came complete with a bonus CD comprising a further 20 previously unreleased covers recorded by Costello in the 1990s. These included such obvious classics as Lennon/McCartney's "You've Got To Hide Your Love Away," Chips Moman and Dan Penn's soul standard "The Dark End Of The Street" and Bruce Springsteen's "Brilliant Disguise," the latter two as part of a private demo for Costello's country hero, George Jones.

But, for the original Kojak Variety, Costello was in full crate-rummaging record collector mode; selecting 15 tunes dominated by obscure album tracks and B-sides from the 1950s and '60s, dominated by soul, rhythm 'n' blues and country, in which only two songs — British dance bandleader Ray Noble's "The Very Thought Of You" and Ray Davies' much-loved "Days" — were not written by Americans.

It's no surprise, then, that the small band chosen to back Costello on this reverent tribute to American roots is largely comprised of US session royalty. Guitarists James Burton and Marc Ribot, drummer Jim Keltner, keyboardist Larry Knechtel and bassist Jerry Scheff are the kind of legends who can include names such as Presley, Dylan, Lennon, Cash, Waits, The Beach Boys and The Doors on their CVs, although Costello also found room for his loyal Attractions sticksman Pete Thomas. What may come as more of a surprise is the almost-offhand nature of the album's genesis.

In 1990, Costello had planned to follow Spike with an album with The Attractions. But the negotiations became, according to Costello's own liner notes for Kojak Variety, "a theatre for delusions and long harboured grudges," and the Attractions reunion was shelved. Instead, Costello decided that a fortnight in the Caribbean with musicians he had worked with in touring band The Confederates and, in Ribot's case, the Spike sessions, would be a lot more fun than squabbling with old friends. Cue two weeks at Blue Wave Studios in Barbados, dodging mongooses and battling with Costello's untimely bout of laryngitis. The odd, Telly Savalas-referencing title came from a grocery store near the studio that Costello felt reflected the arcane, pick-'n'-mix nature of the Kojak Variety material.

Costello wanted label Warner Brothers to just throw the album out as a low-key release somewhere between 1991's Mighty Like A Rose and his 1993 Brodsky Quartet collaboration The Juliet Letters. But major labels don't cough up for trips to Barbados only to slip the resulting sessions out unnoticed. Consequently, Kojak Variety occupies a strange position in the Costello canon: a somewhat out-of-place intermission between Costello's final albums with The Attractions. This affected the confused critical response more than anything else, as fans delighted by Brutal Youth's return to the raging, feral beat-pop of Costello's early days were suddenly expected to get happy about a set that, in places, sounded like a rarefied version of a Jools Holland blues-jam on Later.

Therefore, the opening workmanlike brawl with the Screaming Jay Hawkins B-side "Strange" has you fearing the worst, as do Little Willie John's "Leave My Kitten Alone," a misguided Little Richard impression on "Bama Lama Bama Loo," a messy stomp through Jesse Winchester's "Payday" and gospel-jazz slouches through Willie Dixon's "Hidden Charms" and Mose Allison's "Everybody's Crying Mercy."

But the slower and more feminine the album becomes, the better it gets. The Supremes' "Remove This Doubt" is a gorgeous deep soul weepie, with Knechtel's romantic piano triplets and Costello's own falsetto harmonies keeping the girl-group drama high, despite the lyrics' change of gender. The same androgynous ballad tricks buoy Burt Bacharach's "Please Stay," Aretha's "Running Out Of Fools" and Randy Newman's "I've Been Wrong Before," previously recorded by both Dusty Springfield and Cilla Black.

And although Bill Anderson's "Must You Throw Dirt In My Face" and "The Very Thought Of You" are both male compositions, Costello sings and arranges them with big nods towards the torchy female soul ballads of the '60s, to delicious, sighing effect.

Kojak Variety's two finest moments, however, are exceptions to the in-touch-with-your-feminine-side rule. Costello's confident take on Bob Dylan's "I Threw It All Away" from Nashville Skyline sees him sing it like Lennon over a perfect meld of R'n'B feel and Pat Garrett...-era Dylan arrangement. It's a top-class Costello cover, but still not as thrilling as his spooky, freaked-out take on The Kinks' "Days," in which Costello rediscovers that thick, queasy, nasal voice that made his early records so savage and true (it also sounds oddly like 2014-era Damon Albarn). "Days," with its dislocated dub-psych deconstruction of Ray Davies' elegant nostalgia, is right up there among Costello's finest moments.

On the liner notes for the 2004 reissue, Costello reiterates his regret that Kojak Variety hadn't been allowed to "simply appear in the racks" sometime in 1991, remarking that the album would have "had more charm if issued in this fashion." But Kojak Variety's best moments are sublime, and the whole project echoes a key couplet from its second song: "When I hold you in my arms / It brings out all of your hidden charms."

|

|

Painted From Memory

Rob Hughes

Such unlikely lovers... EC measures his songwriting chops up against an all-time master, Burt Bacharach.

|

They say you should never meet your heroes, much less work with them. Not that Elvis Costello was having any truck with that. Especially when given the opportunity to record with Burt Bacharach on the soundtrack of Allison Anders' 1996 drama Grace Of My Heart.

The film didn't do great, but Costello and his new buddy did. The pair's co-written "God Give Me Strength," played out over the closing credits with a full orchestra, was perhaps the best thing about it. An epic ballad with an impassioned vocal and Bacharach's sure handiwork — discreet piano, soft horns and rousing string choir — it was an ideal excuse for Costello to suggest a full-length collaboration.

Costello had long been a fan. Growing up in the '60s, he'd watched his bandleader father Ross cover Bacharach songs in his setlist. He and The Attractions were playing "I Just Don't Know What To Do With Myself" at the height of punk in '77 (a version cropped up on Live Stiffs the following year). And by the mid-'80s Costello was slipping bits of "I Say A Little Prayer" and "Twenty Four Hours From Tulsa" into live medleys.

Timing was key. With The Attractions no longer a going concern, Costello had spent most of 1997 happily flitting from one guest-spot gig to another: The Brodsky Quartet in Europe, The Mingus Big Band in São Paulo, Ricky Skaggs in Nashville, The Fairfield Four in New York. Though it was to Bacharach, having appeared together on the Late Show With David Letterman in February, that he kept returning. The result was a series of fruitful writing sessions across the year, before the duo were finally ready to record in the summer of '98.

Painted From Memory operated along pretty specific roles. Both parties initially worked on the music, before Bacharach (making his first studio album in 21 years) was left to further refine the melodies and fine-tune arrangements. Costello, as with Burt's '60s foil Hal David, brought the lyrics.

Not a great deal had changed in Bacharach's schooled approach over the decades. These were meticulously crafted songs with a luxuriant touch, their heated drama ramped higher by the use of a 24-piece string orchestra and swathes of horns and woodwinds. Yet this was no ersatz nostalgia trip into some lost era of sophisticated pop. Costello was careful to insist that, at a time when lounge music had been rediscovered by a new generation of kitschy clubbers, this wasn't intended to be easy listening.

It was Costello who gave Painted From Memory its emotional centre. The themes are almost universally dark, disturbed even. Love and loss may have been a Bacharach-David bedrock, but these songs cut deeper, driven by despair, regret, betrayal and self-admonishment. Even when things take a rare turn for the good, as on "Such Unlikely Lovers," it's counterweighted by a sense of foreboding, as if disaster was merely biding its time.

The album offers a gentle clash of styles: Bacharach the classic structuralist, Costello the wordsmith tinkering with form. By the latter's own admission, it wasn't always smooth. He adhered to the exacting standards of Bacharach, 26 years his senior, by constantly pruning his lyrics, cutting away his more verbose instincts and saying only what needed to be said.

In Costello's hands, love appears to be little more than a battleground strewn with debris. Or, more precisely on "The Sweetest Punch," a boxing canvas. "You dropped the band, I can't understand it / Not after all we've been through / Words start to fly, my glass jaw and I / Will find one to walk right into," he sings, as the recriminations fly and the orchestra approximates the dinging bell of the next round.

Absolved of musical responsibilities, having left all that to Bacharach and the rhythm core of Steve Nieve, bassist Greg Cohen and drummer Jim Keltner, it becomes apparent that Costello has blossomed into a truly great singer. "I Still Have That Other Girl" is a slow-sad number freighted with anguish, in which he rises to the high notes over some deliciously supple chord changes and sudden gusts of strings. And though he undergoes the odd wobble on "This House Is Empty Now," with its soft echoes of "A House Is Not A Home," the feeling of contrition is tangible.

As with the above, you can easily imagine Dionne Warwick doing "Toledo," with its deft brass intro, cooing girl chorus and old-school fadeout. The jazz-scented "My Thief" is another consummate exercise in restraint, the song's protagonist clinging to the last vestiges of hope as Bacharach's orchestra sweeps in: "Sometimes I pretend you'll come back again / And you'll console the heart you stole / Have pity on the man / Who knows that you have gone / And has begun to break down."

The sore point of Painted From Memory, however, is a somewhat predictable one. At times it suffers under the weight of its own perfectionism, Bacharach's arrangements slick to the point of uniformity. And for all the natural scratchiness of Costello's voice, you can't help but crave a little more grit. A little more urgency.

Its release came with an aggressive marketing push from Mercury that saw Bacharach and Costello undertake a series of high-profile TV appearances, some full orchestra gigs and a remake of "I'll Never Fall In Love Again" for the second Austin Powers movie. Channel 4 aired a documentary on the making of the album, Because It's A Lonely World, on Boxing Day 1998, with Bravo later following suit in the US. Painted From Memory even won a Grammy for "I Still Have That Other Girl."

Yet none of this seemed to chime with the public on any meaningful scale. Reviews may have been favourable, generally, but the album stalled outside the Top 30 in the UK. In America it just about crept below 80. Maybe Painted From Memory was seen as little more than an anachronism, two artists immersing themselves in the kind of artful songcraft that had long since slipped away. More's the pity, because here you'll find some of the most engaging vocal performances of Costello's entire career.

|

|

North

Nick Hasted

"A change has come over me I'm powerless to express." Disarmingly honest, uncharacteristically happy - this guy's in love!

|

North is Costello's least typical set of songs. It finds the Mouth Almighty tongue-tied, and the launcher of a hundred acid-tipped romantic barbs humbled by love. Laying his strengths to one side, he left himself uncharacteristically defenceless with a muted, soft-hearted, vulnerable album of unmistakably autobiographical songs, tracing the collapse of his marriage to Cait O'Riordan and infatuation with his future wife, Canadian jazz singer Diana Krall. Costello predictably bristled at the wounding reviews that resulted. These weren't unfair, inasmuch as a musician who only made records like North would be a minor one. But in the context of Costello's career, it has the feeling of opening the windows on a cool, bright day and gratefully breathing in, before returning to work in the emotional and verbal hothouse of the MacManus song factory. It's a disarmingly honest pause for thought.

The periodically volatile relationship with O'Riordan (Costello's "spiritual," not legal, wife, his biographer Graeme Thomson revealed) had flared into public rows during the extensive When I Was Cruel world tour. They had separated in September 2002, announcing an "amicable" end to their "marriage" in November. He had met Krall when they co-presented a Grammy award that February, and they had quickly fallen hard for each other. In April 2003, he recorded the songs that this inspired with equal speed, playing what were basically piano ballads with an acoustic quartet including Steve Nieve. A sparingly used 48-piece orchestra was conducted by Costello from his own score, and The Brodsky Quartet and the great jazz saxophonist Lee Konitz also guested.

Costello's previous marriage break-up had resulted in a sonically clogged, cryptic, drink-sodden shambles, Goodbye Cruel World. North mostly drew on one clear strand of his music — the one that had introduced a generation of punks to Rodgers and Hart with "Oliver's Army"s B-side "My Funny Valentine" and recently given him a Japanese No 1 with Charlie Chaplin's "Smile," as well as readmittance to the UK Top 20 with Charles Aznavour's "She." This was a style that could also be traced through Painted From Memory and the low-key loveliness of All This Useless Beauty's "I Want To Vanish." "It isn't a standards-related record," Costello cautioned CMJ magazine. "It has as much to do with the songs I've listened to from the 19th century as songs from the 1940s and '50s. Certainly the emotional language of these songs is much less coded than you would find in the era of Ira Gershwin or Lorenz Hart."

Much less coded, too, than he had previously been himself. These songs are written by a man stunned with love. Their tone is dreamy, concussed, disbelieving, that of someone not quite himself. They fall between eras, writing the blunt romantic confessions of Laurel Canyon singer-songwriters in the style of anonymously wounded song-cycles from an earlier time; Frank Sinatra Sings For Only The Lonely, say. Most remarkably, North is an inarticulate album. As if infantilised by his romance with Krall, Costello's usually jungle-thick vocabulary has vanished. "Someone Took The Words Away," set during the end of the affair with O'Riordan, says this directly. "A change has come over me / I'm powerless to express / ...And if I try my voice will break," he realises. Summoning "my powers of conversation," he can talk to himself, but with the lover he's losing he's baffled and speechless. "All these things I can't quite place / Perhaps they're written on my face?" he hopes. With words uniquely failing a dumbstruck Costello, he hands Konitz the task of expressing his feelings. The saxophonist, who made his name on Miles Davis' Birth Of The Cool sessions in 1949, responds with a quietly conversational, worldly-wise, sadly accepting solo.

North's first half takes us through the meeting with Krall ("You Turned To Me") to "When It Sings"' fond farewell to O'Riordan: "Maybe this is the love song I refused to / Write her when I loved her like I used to." Peter Erskine is all delicate brushwork, the drums themselves barely intruding, as Costello maturely describes his marriage's dismantlement.

Teasing these feelings from North's minimal, static, hushed arrangements requires close attention, and closer interest in a private life Costello wasn't discussing in interviews. The heartfelt gushing of North's Krall-adoring second half tests the patience still more. "Friends now regard me with indulgent smiles / But when I start to speak, they run for miles," Costello knowingly concedes on "Let Me Tell You About Her." The Brodsky Quartet accompany "Still" on its melody's gentle upward curve, an optimistic climb recurring through the rest of the album, which fills with torch songs interesting only for their giddy gaucheness: "I want to kiss you in a rush / And whisper things to make you blush..." These are love letters straight from the heart, rashly posted to the rest of the world.

"There's something indescribable / I still can't catch," Costello puzzles on "Let Me Tell You About Her," as its piano melody pirouettes with lazy pleasure, like Astaire dancing down the stairs in slow motion. The grace notes a Cole Porter could find in breezy love lyrics just won't come. All Costello can manage are the platitudes of any rube who's head over heels. "Someday I wanna hear him duet with Tony Bennett on this song," Al Kooper enthused of "When Green Eyes Turn Blue," but it's doubtful a singer used to Tin Pan Alley's best would bother.

Costello had left himself wide open with North, and the response was chastening. It managed less than half the 200,000 sales of When I Was Cruel's US comeback, and reviews were generally suspicious. Even an attempt to sing "Someone Took the Words Away" with the affable Konitz in a New York jazz club was thwarted, when his bassist refused to share the stage with a rock singer. The borders Costello liked to ignore remained up. "I know that everything on the record is true, and I know that I feel it," he said in North's defence. The simple musical life wasn't really for him. But just once, he had to get happy.

|

|

The River In Reverse

John Lewis

In Katrina's wake, Costello and Allen Toussaint come together for a righteous celebration of Crescent City sounds.

|

When Hurricane Katrina destroyed huge parts of New Orleans at the end of August 2005, one of Elvis Costello's first concerns was for the well-being of his friends in the city — in particular Allen Toussaint, who went missing for several days after the deluge. His house, near the Fair Grounds Race Course, had been badly damaged, while his fabled Sea-Saint studio had been utterly destroyed.

Costello, still unaware of his friend's whereabouts, played the Bumbershoot festival in Seattle on September 5 and closed his set with two Toussaint songs — "Freedom For The Stallion" and "All These Things" — played solo for voice and guitar: "That was just my way of sending out a little message, the way you do with music, not really knowing where it goes."

A week later, Costello and his wife Diana Krall were asked by Wynton Marsalis to play a benefit concert for the victims of Hurricane Katrina in New York's Lincoln Center. By this time, Costello had learned that Toussaint had got out of Louisiana just after Katrina and relocated in Manhattan, and the pair ended up duetting on a version of "Freedom For The Stallion" at the gig on September 17. It was the first of three benefit concerts they'd play together — including one at Madison Square Garden — and Costello quickly decided that it would be a good idea to do a songbook of Allen Toussaint's compositions. Verve Records agreed and, within two months, Costello (and his Imposters) and Toussaint (and his Crescent City Horns) were recording an album together, helmed by Joe Henry. It took them a week at Sunset Sound in Los Angeles and another week in Piety Street, one of the few New Orleans studios to survive Katrina.

Costello had long been a fan of Toussaint's music. As far back as 1974, friends recall Toussaint LPs in his collection, alongside early Toussaint-produced seven-inch singles on the Mint label (for much of the '60s and '70s, Toussaint was the Phil Spector of New Orleans). They first made contact in 1983 when Costello, in New Orleans with the Dexys horn section, approached Toussaint to produce a wonderfully offbeat version of Yoko Ono's "Walking On Thin Ice" (something you'll find on the 1987 compilation Out Of Our Idiot). Six years later, Toussaint was part of the all-star lineup for Spike, lending a Big Easy stomp to "Deep Dark Truthful Mirror." In 1986 Costello recorded Toussaint's "All These Things" during the sessions for Blood & Chocolate; even the Trust-era favourite, "From A Whisper To A Scream," is a nod to a Toussaint song of the same name.

This being Costello, the Toussaint songs here are the choices of an aficionado, not a dilettante. There are none of Toussaint's best-known hits — no "Working In The Coal Mine" or "Southern Nights," no "Ride Your Pony," "Fortune Teller," "Hercules" or "Everything I Do Gonna Be Funky." Instead Costello digs deep to find relatively obscure '60s and '70s sides. The arrangements — anchored around the churchy interplay between Toussaint on piano and Steve Nieve on Hammond B3 — are also entrenched in antique New Orleans R'n'B.

The album opens with "On Your Way Down," a slow-burning, gumbo-fried gospel track originally written for Lee Dorsey in 1973 and subsequently covered by Little Feat. When Dorsey sang: "The same people you misuse on your way up / You might meet up / On your way down," he did so with a mix of resignation and sly optimism, a belief that things are going to get better. Costello has no such illusions, spitting out the lyrics with a measured viciousness that he maintains for much of the album.

The aforementioned "Freedom For The Stallion" is another gospel-ish civil rights song from 1973, dealing with harrowing images of slavery ("Big ships are sailing / slaves all chained and bound") and exploitation ("They got men making laws that destroy other men"). Where the versions by Dorsey, Toussaint and the Hues Corporation had a serene, hymnal dignity, Costello can't hide his anger. Even on "Tears, Tears And More Tears," a jaunty, high-stepping break-up song, Costello sings about betrayal as if he's investigating the ineptitude of FEMA during Katrina. This is an angry album for a New Orleans that had been destroyed by government mismanagement as much as natural disaster.

If Costello, like so many of the singers that Toussaint wrote for, is a big-lunged yelper, Toussaint's own voice is a quiet whisper. That contrast is particularly evident on "Who's Gonna Help Brother Get Further," the only song where Toussaint takes the lead vocal. "Whatever happened to the Liberty Bell we heard so much about?" he sighs. "Did it really ding-dong? It didn't ding long." When Costello reprises the line towards the end of the song, he invests it with a certain English sarcasm.

The post-Katrina imagery becomes even more complex where Costello is writing the lyrics. The title track, which seems to have been built on a slowed-down version of "Hercules" (the classic Toussaint wrote for Aaron Neville), paints the flood as a metaphor for the rightward drift of American politics ("An uncivil war divides the nation"). "Broken Promise Land" glues together an uptempo funk rocker with a Beatlesy bridge, with suitably edgy lyrics ("How high we gonna build this wall"). "The Sharpest Thorn" is a fine waltz — rich in Biblical imagery — which has more than a passing resemblance to "The Scarlet Tide" (from The Delivery Man).

Best of all is "International Echo," which channels the crate-digging soul fan of Get Happy!!, apparently celebrating all those seven-inch singles Toussaint produced for the Mint, Ace and Instant labels ("I felt the pulse in a drum tattoo / Even though I knew it was taboo").

As well as Costello and Toussaint, "Ascension Day" is also credited to Roy Byrd, aka Professor Longhair, and is based on Toussaint's instrumental "Tipitina And Me," which resets Longhair's rambunctious boogie-woogie classic "Tipitina" in a minor key. Here Costello's cryptic lyrics gel with Toussaint's stately instrumental, and the result is his most controlled vocal take.

The album was regarded by many as Costello's most effective collaboration to date. Toussaint certainly benefited, saying that the LP had transformed him from a backroom studio presence into something of a marquee name. "Katrina turned out to be a good booking agent," he said, wryly.

|

|

Secret, Profane & Sugarcane

David Quantick

A sequel to King Of America? Or extracts from an opera about Hans Christian Andersen? EC's schizophrenic 25th.

|

You know how Neil Young does all these albums where the songs don't have any real connection save for the fact that they're on the new Neil Young album? So you'll get two songs from the 1970s, a reworking of a B-side, something new, something from a soundtrack and maybe even an old live recording — a snapshot cross-section of whatever's going through or coming out of the great man's head... Well, that's pretty much how Elvis Costello's 25th album can feel at times. Of course, it's not utterly incoherent, being Elvis Costello, and it reveals its treasures over time like a really slow stripper, but it is at base a collaboration between Mister Hodge and Mister Podge.

On the surface, if you're in a hurry, it's King Of America 2, a collaboration between Costello and T Bone Burnett with a countryish band featuring double bass, mandolin, acoustic guitar, backing vocals by Emmylou Harris and Jim Lauderdale and not any synthesisers. It was recorded in three days, a classic Costello technique for shaking up the juices creative, and it features not one but three bona fide country songs — the gorgeous oldie "Changing Partners" (a hit for Patti Page in 1953), "Hidden Shame" (written by Costello for and recorded by Johnny Cash and also appearing on his 1990 album Boom Chicka Boom) and "I Felt The Chill Before The Winter Came" (written by Costello and Loretta Lynn in Johnny Cash's cabin but not appearing on her 2004 Van Lear Rose album). And there's a new version of "Complicated Shadows," written for Cash in 1996 but not recorded by him). Oh, and on some editions, there's an engaging accordion-powered skip through The Velvet Underground's Cajun classic "Femme Fatale."

All of this would be more than enough for most artists — actually, all this would be more than exhausting enough for most artists — but this is Elvis Costello. And he's written an opera — commissioned by the Royal Danish Opera in 2005 — about Danish national treasure Hans Christian Andersen (an artist with whom he has previous, having ended 1979's "Sunday's Best" with a quick burst of "Wonderful, Wonderful Copenhagen"). Except it's not just about Hans Christian Andersen, it's about Andersen's unrequited love for the singer Jenny Lind, the "Swedish Nightingale." And it's not just about the unrequited love of Denmark's national treasure for the Swedish Nightingale, it's also about Jenny Lind's 1850-1852 tour of America and that tour's promoter, PT Barnum. And it's also about slavery, and to some extent slavery's links to Liverpool. (I haven't heard The Secret Songs — the name of the opera, which also provides the "secret" in this album's title — but I've read some of its excellent lyrics online — there's a great bird pun — and would like to see it. But I digress.)

So, being an Elvis Costello album, it doesn't just contain an album's worth of country songs and Americana numbers old and new, it's got five songs from a Danish opera. (Songs not included from The Secret Songs include "American Humbug," "My Toy Theatre," "Illustrated Lady," "She Was No Good," "The Misfit" and "The Famous Artificial Bird" — great titles all, and with luck we'll be hearing them soon).

Fortunately, also being an Elvis Costello album, the two (or more) groups of songs hang together fairly well, recorded as they are with the same band in the same studio at the same time by the same producer, and thus not suffering from the awful jarring audioclash that several similar attempts by other artists to weld a pony to a mule have suffered from in the past.

You can tell which songs are from the opera and which aren't quite easily — the opera songs often have the slightly atonal quality of Costello's Juliet Letters material as well as lyrics like, "The slave ship 'Blessing' slipped from Liverpool / Over the waves the Royal Navy rules / To go and plunder the Kingdom of Benin / Where certain history ends and shame begins" ("Red Cotton"), while the country songs sound like country songs and have lyrics like, "Well, there's a different kind of prison / And it don't even have to look much like a cell" ("Hidden Shame"). And there are songs whose lyrics and melodies are just unmistakably Elvis Costello, like "My All Time Doll" (sadly only the third Costello song with "Doll" in the title) and "Down Among The Wines And Spirits," the opening track and a song that would have fitted on King Of America like a screwtop lid on a whiskey bottle.

You won't find a classic hit single here, or a ballad that takes your heart out through your rib cage, but this is an album with gradually plumbable depths. There's the fiddling glide of "Crooked Line," with Emmylou Harris and Costello as the Everly Siblings. There's the wonderful return of the Almost Blue croon on "I Felt The Chill Before The Winter Came." On "Sulphur To Sugarcane," there's Costello's sleaziest and most rhyming-dictionary-brilliant lyric since I don't know when ("The women in Poughkeepsie / Take their clothes off when they're tipsy / But I hear in Ypsilanti / They don't wear any panties"). The cover of "Changing Partners" is sincere as can be, and that of "Femme Fatale" is dafter than a village idiot. And the songs from The Secret Songs, while often statelier than a galleon's aunt, reveal their charms and grace over time outside their original context. Messrs Hodge and Podge would be proud.

|

|

Wise Up Ghost

Sharon O'Connell

|

Sharon O'Connell reviews Wise Up Ghost; Sharon O'Connell reviews Wise Up Ghost; Sharon O'Connell reviews Wise Up Ghost; Sharon O'Connell reviews Wise Up Ghost;

Sharon O'Connell reviews Wise Up Ghost; Sharon O'Connell reviews Wise Up Ghost; Sharon O'Connell reviews Wise Up Ghost; Sharon O'Connell reviews Wise Up Ghost;

|

|

|

Cover and page scan.

Contents pages.

My Aim Is True

Peter Watts

Straight out of the lipstick factory, a "complete loser" comes good.

|

When My Aim Is True landed on the desk of American critic Greil Marcus, he "thought it was a hoax." In the rock world of 1977, nobody looked or sounded like the man on the cover, with bully-me glasses, gammy-legged stance, whiney voice and loud jacket. "I didn't believe anyone as geeky, who looked as if he were about to trip over his own feet, would have the nerve to appear in public under his own name," Marcus said when considering the 2001 reissue of My Aim Is True.

In a way, he was right. Costello was the creation of Declan MacManus, born in London in 1954. With a bandleader dad and a mum who ran a record store, MacManus was always going to take an interest in music, and by 1970 he was playing folk clubs before forming a pub rock band, Flip City. In 1975, MacManus had to take a desk job to support his wife and son, and rather than give up on a career in music, this seemed to ignite the single-mindedness that would illuminate his career.