Classic FM, May 1995: Difference between revisions

(formatting) |

(+text part 2) |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

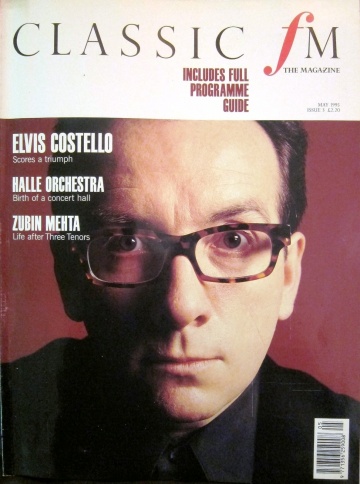

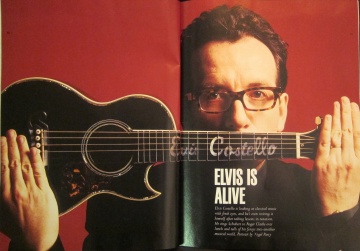

<center>''' Elvis Costello is looking at classical music with fresh eyes, <br> and he's even writing it himself after taking lessons in notation. <br> He sings Schubert to Roger Clarke over lunch and <br> tells of his forays into another musical world.</center> | <center>''' Elvis Costello is looking at classical music with fresh eyes, <br> and he's even writing it himself after taking lessons in notation. <br> He sings Schubert to Roger Clarke over lunch and <br> tells of his forays into another musical world.</center> | ||

{{Bibliography text}} | {{Bibliography text}} | ||

Sitting in a restaurant in Dublin, Elvis Costello is having a go at the dandified London journalists who say he's gone soft after his days as a punk rocker. "It was the ''Brandenburg Concertos'' and Billy J Kramer from the age of eight," he asserts passionately over his angel-hair pasta. "I was never a punk. We were just an unhinged rock 'n'roll band indulging ourselves. Punk had more to do with street theatre than music. But I'm not knocking it." | |||

Nevertheless, most people still see Costello as rooted in the late 1970s. A recent TV advert for ''The Best Punk Record Ever'' showed a clip of Costello as he was, a pigeon-toed, pumped-up Buddy Holly with a fine sneer to his voice and an angular, aggressive stage presence. | |||

Costello is trying to explain he hasn't changed a bit, it's only the perception of him that's changed. "I'm a third-generation musician; my grandfather was a trumpet-player on cruise liners in the 1930s and my father was a vocalist with the Joe Loss Orchestra at the Hammersmith Palais for 16 years. They were really big and did radio and TV broadcasts —London cabbies still remember him. Actually he's got a better voice than me." | |||

His mother worked in record stores and played classical music to her son, who displayed early musical ability but never received any formal training. "I suppose my mother influenced my taste in the field of classical music, though personally I don't accept the artificial distinction between types of music. She played me bits of Mozart and Grieg, tuneful things. She worked at Rushworths in Liverpool, and as Rushworths also sold tickets for the Liverpool Philharmonic, my mother often did overtime working as an usherette at the Philharmonia concerts and smuggled me into a few of them. Even now I'm surprised by who she's seen. I just bought an Artur Schnabel recording and she said, 'Oh yes, I saw him too!'." | |||

With this background knowledge, one is less surprised by Costello's recent forays into the classical field — collaborating with the Brodsky Quartet, raving about Purcell and Monteverdi, working with Fretwork (scoring for viol and counter-tenor voice) and programming for the South Bank's classical music season [[Meltdown|Meltdown '95]]. | |||

Rock stars have often made a stab at classical music. Costello's friend and collaborator Paul McCartney's post-"Eleanor Rigby" experiments have taken him into Liverpool Cathedral, where his Oratorio for 300 voices was performed. McCartney's new piano piece "Leaf" will be performed at the Royal College of Music (helped along by Costello and the Brodsky Quartet) in a charity gig. David Byrne of Talking Heads hired some of Stockhausen's musicians to record the "classical" piece ''The Forest'' in 1992. Frank Zappa worked with composer and conductor Pierre Boulez. Joe Jackson, Annie Lennox and Steve Nieve occasionally let their classical pedigree show. | |||

But Costello is unusual in regarding classical music as a field to be explored rather than merely looted for interesting sounds (we ali know those pop songs, like Procol Harum's "A Whiter Shade of Pale," that are really classical pieces in pop drag). | |||

What's even more unusual is that in November 1991 Costello hired someone to teach him how to write using musical notation. He has since finished several commissions involving complete scores for 13 instruments. "I just reached the point where I had been round the houses a few times with the rock 'n' roll stuff. I had got a bit disenchanted. The sense of new surprises was diminishing and I started to get curious about other areas of music. It all came together when Cait (Costello's wife, the bassist Cait O'Riordan) and I were about to move to Ireland in 1989. One evening we just didn't feel like going to yet another rock concert and getting bored again. So we looked through the paper and picked a venue at random, which happened to be the Wigmore Hall." | |||

Costello's understanding of music is part mystical, part pragmatic. He seeks technical mastery, but has the imagination to wonder why music works. His decision to learn how to score grew from his frustration at being unable to communicate complex musical ideas quickly to the Brodsky Quartet, when they were working together on ''The Juliet Letters''. This collaboration sprang from Costello's frequent attendance of the group's concerts. They met, got on, and almost immediately agreed to do "some sort of project" together. | |||

The result was ''The Juliet Letters'' (themed about letters sent to the Shakespeare heroine). The piece was recorded in Crouch End on analogue tape (like classical musicians, Costello prefers it), and Costello and the four members of the quartet shared the writing credits. "At first, the members of the Brodsky transcribed the things I wrote, and the | |||

{{cx}} | {{cx}} | ||

{{rttc}} | |||

{{Bibliography notes header}} | {{Bibliography notes header}} | ||

Revision as of 15:36, 23 November 2014

|