Hot Press, February 23, 1989: Difference between revisions

(+text part 1) |

(+text part 2) |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

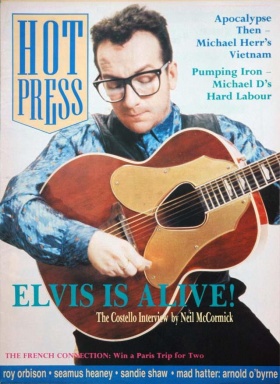

CALL IT coincidence, call it synchronicity. Maybe we should settle for bad planning. I was in Heathrow Airport, waiting to board a delayed Aer Lingus flight from London to Dublin. It was a hastily arranged trip to interview Elvis Costello in the Gresham Hotel. I was skimming through some old Costello articles I had long had on file, not so much in-depth examinations as evasive skirmishes from a time when Elvis spoke to the press infrequently and, it seemed, reluctantly. | CALL IT coincidence, call it synchronicity. Maybe we should settle for bad planning. I was in Heathrow Airport, waiting to board a delayed Aer Lingus flight from London to Dublin. It was a hastily arranged trip to interview Elvis Costello in the Gresham Hotel. I was skimming through some old Costello articles I had long had on file, not so much in-depth examinations as evasive skirmishes from a time when Elvis spoke to the press infrequently and, it seemed, reluctantly. | ||

"The press were looking for something to crucify me with, and I fed myself to the lions," said the singer in a rare 1982 | "The press were looking for something to crucify me with, and I fed myself to the lions," said the singer in a rare 1982 ''[[Rolling Stone, September 2, 1982|Rolling Stone]]'' interview, referring to the petty, drunken argument with Bonnie Bramlett, when Elvis shot his mouth off about black music and then was forced to duck as American journalists returned fire. ELVIS COSTELLO REPENTS said the cover headline over a photo of a completely unpenitent pop-star, gazing suspiciously out through large, black-rimmed spectacles, as if irritated at having to break his self-imposed silence to explain off the unfortunate and unwarranted stigma of racism that was then still damaging his American career. I looked up from the page... and straight into the same face gazing vacantly back at me from across the departure lounge. | ||

The face was a little heavier maybe, slightly bearded, sporting small, rounded, dark glasses and with a black cap pulled low on the forehead as if making a half-hearted attempt at celebrity disguise, but it was him alright. Elvis Costello, in person, his wife Cait sitting to his right, a WEA International rep to his left. Carefully folding my clippings, I ambled over to introduce myself. | The face was a little heavier maybe, slightly bearded, sporting small, rounded, dark glasses and with a black cap pulled low on the forehead as if making a half-hearted attempt at celebrity disguise, but it was him alright. Elvis Costello, in person, his wife Cait sitting to his right, a WEA International rep to his left. Carefully folding my clippings, I ambled over to introduce myself. | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

Elvis has long since made his peace with the press and indeed, it seems, with the world. He is affable and easy to talk to, waxing eloquently on a wide range of musical topics. But the sense of privacy that drove him to keep journalists at arms length for so long remains, and he is evasive if the interview strays too far from his work. "I don't really see what this has got to do with music," he said at one point, signalling an end to a conversation about his family background. To be guarded about his private life and persona is, of course, his prerogative; to choose to probe it is mine. When we settled down to talk in a suite at the top of the Gresham, next door to the rooms he occupied for three months in '87, I wanted to try and find out something about who Elvis Costello really is. I think I found out a little, though an hour and a half was too short a time to talk to the only recording artist in the world whose every record I possess. | Elvis has long since made his peace with the press and indeed, it seems, with the world. He is affable and easy to talk to, waxing eloquently on a wide range of musical topics. But the sense of privacy that drove him to keep journalists at arms length for so long remains, and he is evasive if the interview strays too far from his work. "I don't really see what this has got to do with music," he said at one point, signalling an end to a conversation about his family background. To be guarded about his private life and persona is, of course, his prerogative; to choose to probe it is mine. When we settled down to talk in a suite at the top of the Gresham, next door to the rooms he occupied for three months in '87, I wanted to try and find out something about who Elvis Costello really is. I think I found out a little, though an hour and a half was too short a time to talk to the only recording artist in the world whose every record I possess. | ||

Between 1977 and 1987 Elvis Costello released 11 albums, not including two compilations of obscurities and a ''Best Of''. Throw in an impressive number of collaborations and production jobs and his itinerary for those ten years looks like the wet dream of a workaholic. The two year gap between ''Blood And Chocolate'' and his new album, ''Spike'', is the longest of his career, but, as he explains, "I haven't exactly been holidaying." | |||

He toured sporadically with the loose collection of ''King Of America'' session men The Confederates, "a difficult band to get together in one place at one time." He did get them together in Europe, then later in the southern states of America, in Australia and Japan. "I wanted to play down south with those guys just to see what happened," he says. They played Honky Tonks in Tulsa, New Orleans and Nashville where, he confesses, "the audiences were completely bewildered because they have a force-fed diet of that kind of music, and R'n'B and country, and when I go down there they kind of want punk rock or something!" | |||

In '87 he also did a solo college tour in America and then came to Ireland and lived in The Gresham for three months while Cart was acting in the film ''The Courier''. Elvis kept himself busy writing songs ("I must have written about half this album next door," he recalls) and got talked into doing the music for the film, which he found "quite therapeutic not having to worry about song structures." ''The Courier'' got released in '88 to quite an overwhelmingly negative reception -- Elvis thought that unfair: "It wasn't ''Citizen Kane'' but I don't think its makers thought it was." He did some work with Latin American star Reuben Blades, co-writing songs on his first English language album, played with a veritable galaxy of stars backing Roy Orbison for a special concert and, out of the blue, was asked if he would like to do some writing with Paul McCartney. | |||

They had met on a few occasions in studios and on benefit shows, but, as Elvis wryly observes, "He's not the sort of guy you go knocking on his door saying 'Can I write some songs with you?'" A huge Beatles fan, Elvis had never really disparaged McCartney's solo work as many of his punk contemporaries had. "Even at his most nursery rhymish, there was always something musically redeeming in his songs. I learned a tremendous amount from The Beatles and it's in my songs, it's in me, and he's one half of the partnership that put it there in the first place." | |||

"My father sort of became a hippy when he was about forty. He grew his hair and he started listening to The Jefferson Airplane and things, and that was the only time we disagreed about music. He gave me loads of psychedelic records and I was into Tamla Motown by then." | |||

Two of the songs from the McCartney/MacManus partnership appear on ''Spike'', another was a McCartney B-side and others will be on his next album. "On the face of it it doesn't look like a very likely collaboration but it worked out really good," he observes. "We were strangely compatible. You've got to remember that it's just a guy, you know? I'm at exactly the right age to be really intimidated by it and from time to time I'd look up and go 'God it's HIM!', but I had to put all those thoughts aside, particularly any thoughts like 'these are pretty big shoes to be trying to fill' because it's not Lennon and McCartney. He's Paul McCartney, he's been a solo artist much longer than he's been a Beatle and I'm sure it gets on his nerves to be constantly referred to in the past tense. Whether people find his music less exciting now than it was then, well, it's a pretty tall order to be more exciting! It's like being the King of The World for a few years then having to settle for being the ambassador or something. I shouldn't think it's that easy a job and he's a decent person I must say, very sane." | |||

Elvis made no effort to curb his penchant for Beatle-like licks just because he was working with a Beatle. "The ironic part is," he laughs, "if it sounds like he wrote it I probably did and vice versa. He wanted to do all the ones with lots of words and all on one note and I'm the one trying to work in the 'Please Please Me' harmony all over the place. It was really fun." | |||

Most of the rest of Elvis' time has been taken up with preparing and recording his new album. "There's thirty-two musicians on it and there was a lot of phone calls to make. I must have spent a month on the phone ringing people up trying to find out when they were free and make a schedule to accommodate everyone." This is possibly his most expensive album ever. "I didn't have any more money than I'd had on previous albums," he admits, "but this time I spent it all!" There was a lot of travelling and relocating as Elvis and his two co-producers T-Bone Burnett and Kevin Killen moved between Hollywood, New Orleans, Dublin and London "to get the best possible group to play each song." | |||

From the outset Elvis and T-Bone Burnett had wanted to do something different from previous albums, T-Bone encouraging him to approach the recording with a 'similar abandon' to his ''Courier'' soundtrack. They began to draw up a broad list of instruments, approaching each song as a separate entity. "There is almost different instrumentation on every song," says Elvis. The 32 musicians include such famous names as McCartney, Roger McGuinn and Chrissie Hynde, some of America's finest session players including drummers Jim Keltner and Jerry Marotta, an 8-piece brass band he saw while on holiday in New York with his jazz-loving mother ("she really dug them") and an impressive ensemble of Irish folkies including Christy Moore, Donal Lunny, Davy Spillane, Derek Bell, Frankie Gavin and Steve Wickham. "I think it was worth it if it has come out the way I heard it in my head," says Elvis. | |||

"So all these things add up to the sum of the two years since ''Blood And Chocolate''. Which isn't a long time, it's only a long time for me," Elvis sums up, pointing out that, "The Pretenders have released five albums in the time I've released twelve." | |||

Revision as of 18:50, 14 June 2013

|