|

It was bad enough trying to order a pint as you stood up to your ankles in a swill of flat lager and fag ends — but then, in '76, the band started gobbing at you. Gee whizz. Those were the days. Deke Leonard brings his series on the golden days of pub rock to a climax, with the rise of Punk.

By '76 the first wave of pub rock bands had either broken up or moved on to bigger things. Dr Feelgood were conquering America and apart from Graham Parker and the Rumour and Rockpile, there was little attracting press or record company interest.

Parker and the Rumour were already moving on to bigger venues like the Rainbow and Hammersmith Odeon. "I loved the big places," says Parker, "because I'd always had an incredible problem with monitor systems in the pubs. I hadn't had the background of playing different kinds of places like the Rumour had. My singing style was pretty much go out there and scream at the fuckers. Ram it down their throats. For some reason I was angry and for some reason, whether it was all the things they'd been through in their time, The Rumour were all energy and anger. It was a bit nasty. Everybody used to drink quite a lot. We were fuelled on joints and beer. I couldn't get stoned and do a gig now but in those days you were supposed to. It was just part of it. I haven't reformed; I just don't have a drink before I sing now. I'm half-reformed. Once a week I eat brown rice and vegetables."

Down at the Nashville things were turning a little sour. To supply the pub with bands, Dai Davies had formed an agency called Savage Aries, with Derek Savage, an old friend and business associate, and was soon representing Meal Ticket, Frankie Miller, Deaf School and the Flaming Groovies. They built a circuit within a circuit and began bringing in out-of-town bands in for a week or so.

However, the Nashville was a Fullers' pub and Fullers were not happy. They were footing the bill and began to regard the Nashville as something of a fiscal black hole, and the large crowds as a collection of potential trouble-makers.

"We always made sure that the bands had a good time," says Davies, "but Fullers didn't see it that way. I had to force it onto the contract that bands had to have a crate of beer at the end of a gig. It seems such a small thing nowadays but, at the time, it was a very generous gesture, but all these things I had to fight for."

The constant battle was tiresome and Davies, who hadn't handled a band since the demise of Ducks Deluxe and Brinsley Schwarz, toyed with moving back into management. A year or so earlier he had, by chance, seen a band called the Stranglers.

"I thought they were interesting but really bad," says Davies. "They hadn't got it together as a live band. They came into the agency a few weeks later and we said, 'You need to improve a bit musically. Go away and do every gig you can for a year or so.' And that's what they did. Nine months later they rang up and said they'd done all these gigs and they'd had a couple of line-up changes and they were much better. We went to see them again. I thought they were a cross between the Velvet Underground and the Doors. I thought of it as almost the psychedelic revival arrived early. We signed them to the agency, put them round the circuit, and, eventually, we started to manage them."

One day Malcolm McLaren rang up Davies and invited him to come and see his new band, the Sex Pistols. "They were playing at what must have been the first warehouse party, down in the docks somewhere," recalls Davies. I went, and they were great. I just thought I was seeing an English band that was copying Iggy and the Stooges. I'd been heavily involved with Iggy in the past as his publicist and, on the strength of that, I booked them into the Red Cow, in Hammersmith, and did the process with them, graduating them to the Nashville. Malcolm has written this out of the Sex Pistols' history. He prefers the notion that no venue would take the risk of putting them on, but we put them on in all our venues. Malcolm has always been a very personable, nice guy. It's only in the press he pretends to be sinister. He used to come quite regularly to Brinsley Schwarz gigs; probably not a thing he'd admit to."

"I put the Pistols on at the Nashville with the 101ers as a double bill," says Davies. "They did about eight or nine weeks. Nothing outrageous happened. Loads of people came to see them. They were a younger crowd than usual and a little more boisterous, but nothing special. Ordinary kids would come in once or twice and the next week they'd come in with a funny haircut, because they'd decided to go for it. One girl used to come and see Graham Parker. She was about nineteen, obviously well off, and dressed in smart clothes, and she turned into a punk over the eight weeks that the Pistols were there. The smart clothes went, she bought a motor-bike, and her accent switched down to Fulham. She seemed fairly typical.

"There was no trouble until the very last week," remembers Davies. "They staged a rather phoney fight and there was a journalist there to take a photo of it. It wasn't a real fight. We'd had much worse than that. Drag nights were worse than that. Brian, the doorman, who was the best at his job I've ever seen, didn't even notice it. But when it was in the papers, Fullers rang me up, completely outraged. The papers had rung them up and they said, 'We're certainly not having them back, or any bands like them'. The papers rang me and I said, 'It was nothing. They can play here any time they like.' We carried on putting punk bands on, but we had to pretend they weren't punk bands. We had to pretend that the Damned weren't punk. It was certainly a myth that the Sex Pistols were banned from every venue in London. They progressed quite normally through the Fullers' chain. It was their last night at the Nashville, not because of the fight, but because we could not longer afford to book them. They were too big."

The Sex Pistols, however, didn't get past the door at the Hope & Anchor. They sent down their representative, Bernie Rhodes, to fix up a gig. "He was a little turd," says John Eichler, the landlord. "He laid this really obnoxious trip on us about how the Sex Pistols were going to be the next big thing, so I physically threw him out."

Eichler had just taken over the Hope after the previous landlord, Fred Grainger, a dedicated hedonist, had quit to pursue his grandiose dreams.

Eichler was an old colleague of both Dai Davies and Dave Robinson of Stiff Records. He had been one of the protagonists in the Brinsley Schwarz hype' and went on to manage Help Yourself, a United Artists' band who were a refuge for several wayward Ducks Deluxers, and was a member of what was fondly referred to as the UA Mafia who treated Andrew Lauder's A&R office as their own, while Lauder looked on benignly.

Eichler went to see Davies and Savage and together they decided to take over the tenancy of the Hope. Davies and Savage provided the money and Eichler proceeded to rtaVffie pub as he damned well pleased. It's alrbaOy formidable reputation was enhanced by an idiosyncratic booking policy (bands were booked for the most whimsical of reasons), a colourful staff (space cadets and out-of-work actors), and an open-house policy that made the pub the last stop for musicians who had run out of places in which to lig and needed somewhere to crash. Rat Scabies, of the Damned, spent many a night there.

"The Captain and I would go out and, when everywhere else had shut down, it was, 'Let's go down the Hope,' says Scabies. "There was a big room with beds in it. It was like a dormitory for well-dodgy musicians. I remember Jean-Jaques Burnell waking up one morning and doing his karate exercises, and we were all going, 'Aw, fuck off, Burnell'."

For The Damned, getting on the pub circuit wasn't easy, even if they got past the front door.

"We played the Nashville once," recalls Scabies, "and they banned us. We never played there again. It was strange because we used to drink in there, but they wouldn't let us on the stage. The Pistols played there a few times and I think it had upset their customers. Tuesday was Punk night. They were trying to keep that one-night-a-week thing. Monday would be Country & Western, Tuesday would be Punk, and Wednesday would be a stripper, or whatever. They used to try and do that everywhere. We played at the Red Cow once and they said, 'No, never again.' I think the audience was quite a lot of trouble for them. Dire Straits, for example, were there for years doing that circuit, and everybody used to sit there and drink their beer and watch them, and it was all very civilised. Then, suddenly, there were all these little hooligans going, 'Waurrgh!' There were all these little oiks down the front, looking very strange. People were getting up and dancing and I don't think they'd seen that for a few years. And there'd be loads of broken glasses." "Also there was quite a lot of destruction and chaos going on, and on the stage. We were saying, 'It doesn't matter if you boo or throw glasses at us because that's better than taking it calmly. We're not here for that. We are here to incite."

"We did a Punk Festival in Mont-de-Massant, down in the south of France, and Eddie and the Hot Rods and us were the only two bands that vaguely resembled Punk. The rest were all the old hippies. That's where we met Nick Lowe, Sean Tyla, and all that lot. And that's where we met Jake Riviera. We'd heard about Jake through Nick Kent, the NME journalist, who said that he was an on-the-case bloke, who had just started a small record company called Stiff, and he was worth meeting. He was on the case and he did have the right attitude to work with us, so it just fell into place."

Once in the Stiff stable, Riviera and Robinson, far from curtailing the band's excessive behaviour, goaded them on.

"They encouraged us every step of the way," says Scabies. "You wanna smash the drums up, Rat? Go on then. Kick the fucking shit out of them. I'd say, 'Dave, can I set fire to my drums?' and he'd say, 'Use my lighter, Rat.' I think you have to admire Robinson for his gall and his cheek. I don't know how much he's done me for, but I know it's a few quid. Bastard! How he can live in a quarter of a million quid house a quarter of a mile from my two-bedroomed flat, I'll never know. Still..."

With Robinson directing, they shot the "New Rose" video at the Hope & Anchor. "That was one of the first group videos," says Scabies. "I think Jake actually realised that that was the way it was going to go, smart-ass git. And it was cheap, as well as being a new angle, which Mr Robinson was always looking for."

The Hope & Anchor was also the site of one of the Damned's more memorable gigs. "We did it the night after we got kicked off the Anarchy Tour," says Scabies. "Everybody was really fed up because of all the business that was going on with the press, and just to go down and play the Hope again was great. Loads of people turned up."

Charles Shaar Murray, the NME journalist, who himself played the pubs as his alter-ego, Blast Furnace and the Heatwaves, was there. 'They wanted a place to play because it was the only way they could explain to their audience what was going on, so the pubs were part of the life-support system at that point."

It was quite a social occasion. "Chrissie Hynde and Sid Vicious were there," remembers Murray. "At the time Chrissie was in danger of getting slung out of the country and had to marry somebody in a hurry, and Sid had volunteered. Chrissie can count herself extremely lucky that she managed to get her visa sorted out in some other way."

Dai Davies, meanwhile, was trying to sell the Stranglers to United Artists but Andrew Lauder, the head of A&R, was unimpressed.

"Dai gave me a hard time and wouldn't take no for an answer." says Lauder. "He kept bringing in tapes which sounded a bit like the Doors, but, having been to Damned gigs, it didn't seem quite the same idea at all. Dai made me go and see them about six times and I'd keep saying, 'Dai, I don't really see it.' At the time, everybody was trying to decide who was punk and who wasn't. The Sex Pistols and the Clash were punk, the Damned were too light-hearted, and the Stranglers were old farts. In the end it was so damned catchy we went and did it."

"Their gigs were fun," recalls Lauder. "It was all 'Punkrock-Shock-Horror-Stop Show!' That was good for them because their first album appeared at number four in the charts, and everybody fell over. It came out about a week after the Clash album, which had gone in at number twelve, and everybody at CBS was feeling very smug until the Stranglers went in at four, and it was, 'What scam have you pulled here? The bugger is selling!' Nobody was more surprised than UA Records."

The initial reluctance of landlords to book punk acts was overcome when they saw the profits being made by those pubs who did. There was also a growing realisation that, while punks were noisy and boisterous, they were not, with a few notable exceptions, a bunch of psycho-paths. The flood-gates opened and soon the circuit was home to bands such as Siouxie and the Banshees, the Jam, the Vibrators, the Buzzcocks and 999. But although punk was everywhere, there were other things happening.

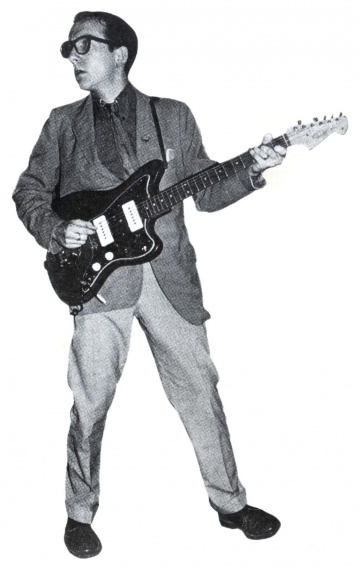

The night Elvis Presley died, Jake Riviera and Nick Lowe were having a drink in the Hope & Anchor. Riviera had just signed Elvis Costello to Stiff, and Costello's first record was attracting attention. The news of Presley's

|