|

Listening to Elvis Costello is like walking down a dark, empty street and hearing another set of heels. His music doesn't make you dance, it makes you jump. It doesn't matter that he's stalking his obsessions and not you, because nobody ought to be this sure of his obsessions. But Costello appears determined never to reach that age when, as Joan Didion once put it, "the wounds begin to heal whether one wants them or not." This Year's Model, his second album in less than a year, is Costello's attempt to make certain those wounds stay open.

Elvis Costello feeds off terror; sometimes it almost seems as if he deliberately conjures it up so he can finger its jagged grain and twist its neck. On last year's My Aim Is True, the fear centered on failure ("Mystery Dance") and rejection ("I'm Not Angry"). On This Year's Model, it zeros in on success: Costello is afraid that fad and fashion will seduce and trample him. "(I Don't Want To Go To) Chelsea" is the title and refrain of his recent Top Twenty single in England, and he means those words to be taken literally. Chelsea represents Costello's nightmare world of success, where deceit is masked by propriety and last year's model is thrown out with yesterday's wash.

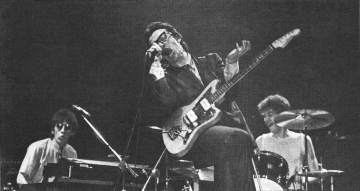

Costello, of course, was last year's model. My Aim Is True was the biggest-selling import in America and later, the first New Wave LP to crack the American Top Fifty. Elvis Costello can describe Chelsea with such precision because he knows — or, at least, doesn't deny — its splendour. If the disdain in his voice appears a little too measured ("I don't want to go to Chelsea / Oh no, it does not move me / Even though I've seen the movie"), it's because it takes all of the singer's resolve to resist Chelsea's temptations. For all his surface cockiness, Costello is a man who's trembling underneath, a man so suspicious of the world that it doesn't matter whether you're bearing gifts or a blackjack, because he's not convinced it makes a difference. The music on This Year's Model twitches in breathless stop-and-go drum bursts, in the nervous arcs of Costello's guitar, in the ominous drone and interruptions of the organ. I don't think there's been a rock 'n' roller who's made fear so palpable or so attractive.

About the only thing wrong with the American version of This Year's Model is that it doesn't include "(I Don't Want To Go To) Chelsea" or "Night Rally," the two additional songs on the import. While This Year's Model doesn't diminish the prodigal brilliance of My Aim Is True, the new record is musically and thematically more of a piece. Costello has all but dispensed with the self-conscious references to rockabilly, country music and early Van Morrison and Bob Dylan that framed his debut. He and his three-piece band, The Attractions, play with a gutty immediacy that makes influences irrelevant. In the organ, which played a minor role on the last album, Costello has found the perfect instrument to shape his sound. It covers the bass and drums like a black fog, compressing everything and forcing his guitar to cut through the songs with calculated, short slashes. Even the drum breaks — the airiest moments on the LP — that punctuate most of the numbers can't bust open the seams. One of Costello's favourite devices is to fade slowly into a song and then abruptly jump out when the action is at its height. This is one of those tricks that make a cut resonate long after it's over, but it's also the ideal metaphor for Costello's antiheroic style. He simply refuses to glamorize himself.

From the beginning, Elvis Costello has insisted that he wants rock & roll success on his terms or not at all. In a way, this makes him a heroic figure, I guess, except that most of the time he refuses to accept even that. On This Year's Model, Costello is brutal toward everyone, but what saves him is that he's just as brutal toward himself. Which means that he can play Charles Bronson to his own Anthony Perkins, that stoic and stutterer become one. It also means that Costello, for all his anger and hostility, can express empathy for whomever he's going after. On "Stranger In The House" (the 45 that was included as a bonus with the initial English pressings of the LP), Costello cooly dissects both himself and the collapse of a relationship. He's so distant he takes on the woman's point of view: he's not a stranger because he's been ostracized, but because he's become a zombie. The uninspired country instrumentation on "Stranger In The House" makes it the most musically conservative song the singer has ever recorded. But the song itself makes absolutely blatant the sexual warfare that lies at the heart of This Year's Model.

If he weren't his own harshest critic — if so many of the wounds weren't self-inflicted — perhaps Costello could be considered a rock & roll bounty hunter, ready to bag anyone if the money's right. But Elvis Costello never gets the girl. For all the immediacy of his emotions, all the romances on This Year's Model are either about to happen or are over, and he's caught between picking up the phone or slamming it down ("No Action"), between rejecting all compromises and trying to come to terms ("Lipstick Vogue"). "I don't want to be no goodie-goodie / I don't want just anybody / I don't want anybody sayin' / You belong to me" he sings at one point, blowing away years and years of pop tradition. But by song's end, he turns around and repeats "You belong to me" over and over again.

But there's something else here. If Costello's music is really frightening, it's not devoid of joy — or, for that matter, humour. This Year's Model has the triumph of an adrenalin kick: "The Beat" or "Pump It Up" are not titles chosen randomly. There's bravado in the way Costello's machine-gun mouth sprays out each image, but like all obsessives, he has to get the details right, connect them through the sheer force of his will. So he's reeling and running, shooting from the hip but taking careful aim. He's ready to challenge all comers, it doesn't matter whether it's the rock & roll industry ("Radio Radio") or the National Front ("Night Rally"). "Don't you know I'm an animal," he sings on "Hand In Hand." But later, in "Lipstick Vogue," he amends that: "Sometimes I almost feel just like a human being." Taken together, these are the words of a brutally honest optimist. Damon Runyan once suggested that life was basically a six-to-five proposition against. I suspect that Elvis Costello would consider those good odds.

|