Uncut, June 1997: Difference between revisions

(+more text +more images) |

(+more text) |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

{{Bibliography article header}} | {{Bibliography article header}} | ||

<center><h3> Armed Forces </h3></center> | <center><h3> Armed Forces </h3></center> | ||

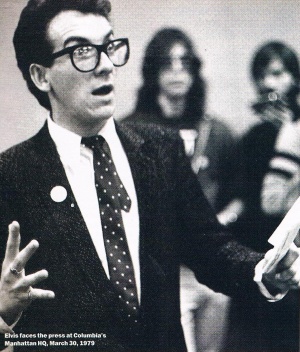

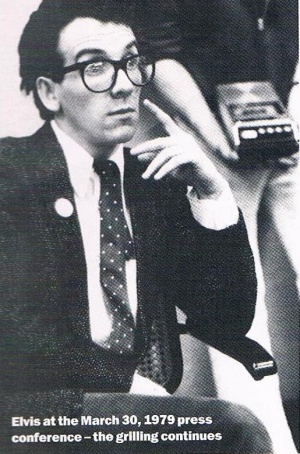

<center>''' The full story of Elvis Costello's <br> | <center>''' The full story of Elvis Costello's calamitous <br> 1979 American tour </center> | ||

---- | ---- | ||

<center> Allan Jones </center> | <center> Allan Jones </center> | ||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

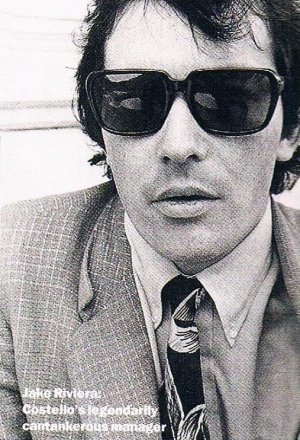

This was an example of a heavy-handed line in provocation that had been patented by Jake and which had since become familiar to anyone who'd come across the Riviera-Costello circle during one of their more intolerant ranting moods. Most people, finding either Jake or Elvis on course for this kind of volcanic verbal onslaught, very sensibly kept their heads down until the storm blew itself out and conditions returned to normal. What you didn't do was show any visible sign of being upset. This only encouraged them. | This was an example of a heavy-handed line in provocation that had been patented by Jake and which had since become familiar to anyone who'd come across the Riviera-Costello circle during one of their more intolerant ranting moods. Most people, finding either Jake or Elvis on course for this kind of volcanic verbal onslaught, very sensibly kept their heads down until the storm blew itself out and conditions returned to normal. What you didn't do was show any visible sign of being upset. This only encouraged them. | ||

Stills and his party unfortunately fell for the whole routine and became immediately defensive. At which point, Costello upped the tempo and apparently dismissed the entire American nation as "just a bunch of flea-bitten greasers and niggers." This was bound to cause the uproar Costello was looking for, and of course it did. One account of the incident has a member of Stills' crew grabbing Costello by | Stills and his party unfortunately fell for the whole routine and became immediately defensive. At which point, Costello upped the tempo and apparently dismissed the entire American nation as "just a bunch of flea-bitten greasers and niggers." This was bound to cause the uproar Costello was looking for, and of course it did. One account of the incident has a member of Stills' crew grabbing Costello by the scruff of the neck and telling him in no uncertain terms to keep his mouth shut, of which there was by now ''no'' chance. Costello had gone too far to back down. According to a report in the ''Random Notes'' pages of ''Rolling Stone'', Costello now turned his attention to Joe Lala and called him "a greaser spic." Stills is then supposed to have grabbed Costello and given him a good shaking before storming out of the bar, angry and disgusted, with Bruce Thomas yelling "Fuck off, steel nose!" after him — the latter remark being an ill-concealed reference to the surgery Stills was alleged to have undergone to repair his nose after a lengthy addiction to cocaine. | ||

The argument now centred around music. with Costello badmouthing most American acts he could think of, including Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly. Bramlett accused him of stealing and plundering from America's rich heritage of black music. citing James Brown and Ray Charles specifically. Costello then contemptuously dismissing James Brown as "a jive-ass nigger". | |||

This was insensible on Costello's part, and even in the depths of his staggering drunkenness he should have known that he was pushing it too hard, too far. But he blundered on, the hole he was digging for himself getting deeper and darker with every ill-considered remark. | |||

"All right, you son of a bitch," Bramlett demanded, incensed, "what do you think of Ray Charles?" | |||

"He's nothing but an ignorant, blind nigger." Costello seethed venomously, beyond legitimate defence now, mischief turning to malice, a litany of brutal abuse. Bramlett was appalled, and told him to keep his damned opinions to himself. | |||

"Fuck Ray Charles." Costello allegedly roared, "fuck niggers. and fuck you!" | |||

This was too much for Bramlett. | |||

"Don't put the tongue on Ray Charles," she yelled, taking a swipe at Costello that according to one report dumped him arse-over-shoulder onto the carpet. Costello would later contend that Bramlett's punch was wild, didn't connect, that he was, in fact, set upon by no less than five of Stills road crew who beat him to the floor, at which point a full-scale brawl broke out. When the warring factions were eventually separated. the Stills party was hustled out of the hotel to their waiting tour bus while Costello stumbled to his room nursing an injured shoulder. | |||

The next day, the ''Armed Forces'' tour moved on to Cleveland, where Costello turned up at a concert by country singer Nicolette Larsen with his arm in a sling; the result, he told fans, laughing it off, of a bust-up over a drink with Bonnie Bramlett. This was typical of his immediate reaction to the fracas in Columbus. which he seems not to have taken terribly seriously. | |||

Talking to people he knew about what had just happened, Costello was determined to play it down, make light of the entire event. The photographer [[Special:WhatLinksHere/Roberta Bayley|Roberta Bayley]], who had known Costello since 1977 when she did a photo-session with him during the recording of ''This Year's Model'', clearly remembers hearing about the incident within 24 hours, from Elvis himself. He described it as a simple bar brawl, an insult match." she later recalled. "He just said, 'I had a fight in the bar last night with these obnoxious people.' No big deal." | |||

For the first few days. at least, after the fracas in Columbus. Costello might well have believed that he'd got away with it, that there would be no public repercussions; that he wouldn't have to answer for what he'd said during his poisonous tirade, that his remarks wouldn't rebound on him in the most terrible way. If this was the case, Costello had reckoned without Bonnie Bramlett, who certainly wasn't prepared to forget what had been said, what had gone down in those awful drunken minutes in the Columbus Holiday Inn. What Costello didn't know, as the ''Armed Forces'' tour swung towards Boston and New York, was that this vengeful woman had already been calling virtually every newspaper, wire service and magazine on the East Coast, giving them explicit details of his outburst, branding him a racist and a bigot and demanding retribution. Costello didn't know it then, but there was going to be hell itself to pay for what he'd said. | |||

The first posters appeared in New York the week after the debacle in Columbus. "ARMED FORCES' LAND IN NY!!!" they shrieked. "WHERE WILL YOU SPEND ELVIS COSTELLO WEEKEND?" they wanted to know. There were two dates stencilled beneath a portrait of a typically brooding Costello: "MARCH 31/THE PALLADIUM. APRIL 1/NOWHERE..." | |||

The poster campaign was part of the graphic overture to what would soon become known as the "April Fool's Day Marathon". It was Jake's idea, of course, and the plan. as usual, was outrageous: six gigs in three days. starting with a concert at the Capitol in [[Concert 1979-03-30 Passaic|Passaic]], New Jersey. backed-up by two shows the next night at the [[Concert 1979-03-31 New York (early)|Palladium]] in New York, followed on Sunday, April 1, with three New York club dates. beginning at six that evening at the [[Concert 1979-04-01 New York (1st show)|Lone Star Cafe]], moving on for a performance at nine at the [[Concert 1979-04-01 New York (2nd show)|Bottom Line]], and ending with a midnight appearance at downtown club called the [[Concert 1979-04-01 New York (3rd show)|Great Gildersleeves]]. | |||

Jake had devised this unprecedented blitz as the grandstanding climax of the ''Armed Forces'' tour. It was essentially a massive publicity binge, intended to overwhelm New York, capture the city's imagination like nothing else in recent memory and grab every available headline for Costello. | |||

If it hadn't been for what had just happened in the bleak precincts of Ohio, Riviera might even have pulled it off, securing Elvis' future celebrity. | |||

By the time Costello arrived in New York, however, the full story of the Columbus brawl was already breaking. The New York press was less concerned with where, when and how often Costello was going to be playing that weekend than they were with what he was supposed to have said two weeks earlier to Bonnie Bramlett. | |||

The first published accounts of the Columbus incident had appeared in New York's ''Village Voice'' and ''Rolling Stone''. These had been followed by reports in ''[[People, April 23, 1979|People]]'' magazine and national and local newspapers. From these, Costello had emerged as a sinister bigot. The East Coast media was outraged by Costello's fiercely disparaging comments about America generally, and James Brown and Ray Charles specifically. By the end of March, they were whipping themselves up into a frenzy of liberal indignation, demanding explanation, public apologies and retractions of what they had already decided were Costello's racist views. | |||

"It was just incredible," recalls Kurt Loder, at the time a senior writer on ''Rolling Stone''. "When I first heard about what was supposed to have happened, it just sounded like a really put-up job. I couldn't imagine that Elvis would ever genuinely think that Ray Charles was a blind, ignorant nigger, but there were people, you know, who wanted to lynch the guy. | |||

"I don't think anyone really believed all the stuff that was coming out. I don't think anyone really believed that Elvis hated niggers, blind or otherwise, but because of the attitude he'd had previously towards the press, he really set himself up. He should've known that if he said anything out of line, it was going to get blown up into a really big thing and that they'd really go for him. Which, of course. they did, and it hit him real hard. Because of who he was and this real hands-off attitude he had, there were some people, definitely, who were ready to push him on this one. | |||

{{cx}} | {{cx}} | ||

| Line 80: | Line 122: | ||

'''Uncut, No. 1, June 1997 | '''Uncut, No. 1, June 1997 | ||

---- | ---- | ||

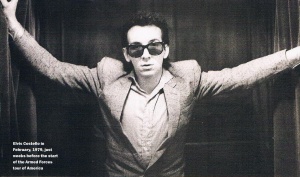

[[Allan Jones]] | [[Allan Jones]] documents the [[:Category:Armed Funk Tour|1979 US tour]]. | ||

{{Bibliography images}} | {{Bibliography images}} | ||

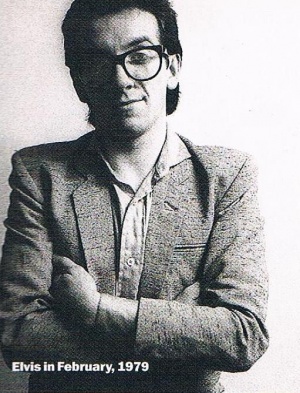

Revision as of 00:26, 24 July 2013

|