—

|

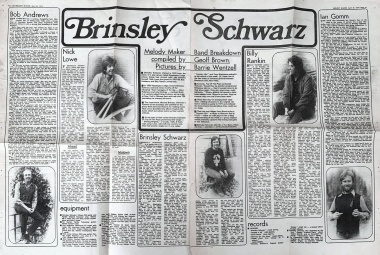

Brinsley Schwarz

Geoff Brown

Melody Maker band breakdown compiled by Geoff Brown

|

Brinsley Schwarz started in 1970 from the ashes of a pop group called Kippington Lodge, whose lineup had started with just Brinsley himself. Nick Lowe had joined in 1967-68; Bob Andrews and Billy Rankin joined later.

In 1969 Kippington Lodge became Brinsley Schwarz and took three months off for rehearsal. Their managers of the day — Dave Robinson and John Eichner — involved them in a venture called Fame-Pushers, set up a gig at New York's Fillmore East and took over 100 journalists to witness the event.

The experiment affected Brinsley Schwarz's outlook on the business and clarified for the group their personal reasons for making music. Nick Lowe described one effect it had on the band, which just about sums up their current attitude.

At the start of their career Brinsley had been on Top Of The Pops promoting their single, "Shining Brightly," a Crosby, Stills & Nash type song. Later, still well into country rock, they had another single out. It was called "Country Girl" and Tony Blackburn picked it as his record of the week. (It's been one of the few areas of common ground between Blackburn and John Peel).

Anyway, Top Of The Pops contacted Schwarz. Would they do another programme? Brinsleys said no — they'd vowed never to do that show again. They got, says Lowe, really righteous. "What a ghastly hit record to have been labelled with. Straw in our hair. Soon as summer was over we'd have been dead."

Since then they've changed their style often. Adding influences to the original, Ian Gomm joined on guitar in 1971 and widened the instrumental combinations they could use on stage.

Their set now ranges from Band-style to "Country Girl" to blues to Motown and to R & B — either an oldie played with a deep understanding of the mode or a group original which precisely captures the feeling and spirit of the influence.

Brinsley Schwarz play like a live disco. Meet the first — and last — of The Great Eclectics.

|

Bob Andrews

|

Bob Andrews has a serious, thoughtful face. Hair recedes like an ebbing tide. Talks with a strong hint of Northern accent and plays keyboards with Brinsley Schwarz with a strong hint nowadays of Garth Hudson.

Bob's been with the guys who formed the basis of the present Brinsley Schwarz for about six years. Before that he was playing with P. P. Arnold.

"It didn't last very long. I got it through a friend of mine. I was having, uh, emotional things at the time. I won't go into that." He smiles.

He, like Ian Gomm, saw an ad in the MM. Went along to an audition and joined the band. "That was Kippington Lodge. They were just issuing their last single. I just got in to be able to sing on the last single. We did a very Joe Cockerish version of 'In My Life,' John Lennon's number. That didn't do anything at all."

Bob started playing in groups when he was 14. Played bass guitar for a year back home in the Leeds area, then he played lead guitar for a year ("I thought I was Chuck Berry.")

Then when he started work some of the lads at the office he was in had a group. "They wanted an organist. I'd played piano when I was younger and so I suddenly fancied the idea of playing organ. Then because we were so together in the works we were forever talking about music, eventually it got intolerable. So we thought let's blow it."

They turned professional. Andrews leans forward against the table throughout the interview. Recollections well up inside him; he smiles at each remembrance. He speaks quickly, in bursts.

"We did one of those auditions 'Groups for continental work,' you know? We did this show with Al Read, a Christmas sort of thing for the Rhine Army. We did the backing. He used to do these sketches where he'd have musical introductions. Like he used to do a football sketch and we'd do the Sports Report theme." He sings it.

Bob stayed in Germany for about two years ("twelve hours a night and stuff") and then he returned to England and got the gig with P. P. Arnold, this was, of course, after her first band, The Nice, had left her to go it alone.

When he joined Kippington Lodge, Bob says the music was getting away from the singles thing ("like when I joined the organist I replaced went and joined Vanity Fare.") Bob, at the time, was leaning towards jazz "and I was also into, well heavy rock I suppose. I'd gone through all the Cream sort of syndrome.

"Then round about the end of 1969 we got the album Crosby, Stills & Nash and I think that was probably one of the biggest things that happened to us before Brinsley Schwarz. That was the sort of thing that changed our way of thinking."

They were, says Bob, getting so far into these new ideas that they were getting fewer and fewer gigs. "It ended up that we just weren't a viable proposition. We had a few fans in our local area (Tunbridge Wells) but you can gig your area only so much.

|

Nick Lowe

|

If Brinsley Schwarz have a front man then it's Nick Lowe. A spiky crest of hair, nose of the type referred to in polite circles as "strong," Nick Lowe plays bass and does much of the lead vocalising, left leg pumping up and down like a man blowing up a flat tyre with a foot pump.

Nick's also their potential hit man. He does most of the band's writing. Of the many songs he's written so far I guess you'd call at least half-a-dozen very good. Two or three are simply excellent. One day he'll write a big hit, but there's no real hurry.

His songs may well be the greatest beneficiaries of Dave Edmunds' production work on the current album.

The band's development started with Nick and Brinsley at school in about '63-'64, the time of the Beatles and the Stones. "Then when we left school there was a gap while we were in semi-pro groups."

Later Brinsley called Nick one day, said his bass player was leaving and did he want the gig. "This was down in Tunbridge Wells, about '67-'68. I left home and we've been together ever since then."

When Nick joined the band, Kippington Lodge, they'd just made "Shy Boy," one of the singles they did for Mark Wirtz, who did the "Teenage Opera" thing.

"He was amazin'. Just way ahead of his time no two ways about it. If he came along nowadays he'd be a Phil Spector sort of character, that's the way I see him."

When he first started Nick played banjo. "I was really into skiffle. In fact I played at one time with Sean Tyla (Ducks Deluxe). I never knew the names of the guys I was with. For some reason in those days you never used to know the names of the guys you were in groups with. I played with Sean in a group called The Four Just Men."

When he started playing guitars in a Kingston Trio type group. "The Shadows, even though I liked them, were a bit before my time but when the Beatles came along I got interested in groups. The only reason I played bass was that it was the only instrument I could join Brinsley's group on."

Nick's early bands, experiences in music included backing singers. J.J. Jackson was one. Billie Davis was another.

Bass playing and singing aside Nick's most important contribution to the band is as songwriter. The first song he recalls writing was a skiffle number.

"I'd heard all the songs about 'The Rock Island Line' and 'The Grand Coolie Dam' and all that and so when the Great Train Robbery was done I wrote a hokey skiffle number about that. Most embarrassing."

Nick says he has little trouble writing a song. "I can't help but write. It's not clever. I just hear things come into my head and I try to go through with them, play 'em.

"What is hard is getting it arranged and constructed in your mind so you can say to somebody 'Look if you play that and I play this I think it's gonna sound like that.' That's the hard part.

"I'm really trying to write a Good Song that'll appeal to anyone. I'd like to get a song that won the Eurovision Song Contest cos I'd make it so drek, so crass, so crap that it'd be great. It would be fantastic.

"I could really get off on doing that, even though I knew it was crap. Cos, you know, you're competing against people there that really know their business. That's hard to do."

"So I play – partly because I'm the singer and partly because I like the style – I play a very simple bass style It's the most effective for Schwarz he adds.

"So I've been influenced I'd say by Paul McCartney of the English bass players but apart from that the bass players I like — as any other bass player will likely tell you — are either Motown and soul bass players because they're so direct. They seem to be able to play just the right thing."

How does Nick feel about the old Brinsley albums? "Well I get off on 'em cos because ... it's hard to say. I can't listen to them in terms of 'dig 'em'.

There're no strict rules with Brinsley Schwarz "There's no way people can categorise us. The way we feel at the moment if something takes our fancy we'll just do that for a while then we'll just change our minds and do something else. In a way we're in a very lucky position."

|

Brinsley Schwarz

|

Brinsley Schwarz is a group and it is a man. Brinsley is a quiet guy. He speaks in a voice so soft as to become almost inaudible. He is a contemplative man. But pleasant and friendly into the bargain. Normal, really.

Though the group has his name he stays in the background, yet one gets the feeling from seeing them work in the studio that his word (if anyone's) will be the final one. He has a definite and authoritative presence.

Brinsley plays guitar, sings harmony, plays a touch of keyboard and has recently added tenor sax.

He started playing 12 years ago, when he was 14. "The Shadows. That's what I was into at first." At the time he was at Woodbridge school in Tunbridge Wells with Nick Lowe.

He played with Lowe in school groups. "Did he tell you about it? ... well, I was in a group in the Wells and we had an argument with the bass player and he left ... or we threw him out ... and then Nicky came down."

How did Kippington Lodge come to be signed by EMI? "Well our manager at the time went round to talk to the record producers in companies and Mark Wirtz said he'd like to listen to us."

Wirtz presumably liked what he heard. "He signed us as his sort of act, you know.

He saw the band live or heard tapes? "Tapes, yeah. I don't think he was too worried who it was, he had some songs ... ideas and stuff for a group which were way ahead of their time. Mainly to get a group to play something which wasn't their own. He had a definite idea of what people would sound like."

"Shy Boy," Kippington Lodge's first single, was about the nearest Wirtz and Brinsley's group got to capturing this sound. A record played on by session guys, the Ivy League even did the vocal harmony. All the group was needed for was lead vocal and pretty faces.

It was the first of many brushes Brinsley's had with the business and each one had, I think, only helped to compound those facets of his character which instinctively avoid publicity.

Kippington Lodge "just went sort of downhill really. The records didn't get off and we got very tired of doing what managers told us to do.

"So, anyway, we in the end just jacked it in. Just stopped. "Then we started again. That's when we met David Robinson in 1970."

One of the other aggravants which has caused Brinsley a certain amount of heartache until now he's just plain fed up with it is the American thing. The Fillmore trip.

After all it was still his name on the posters billed under Quicksilver Messenger Service and Van Morrison outside the Fillmore East. Does it make him as bored as it seems to?

"Well not really, I could go on talking about it for the rest of my life really. Without any trouble. It's just one of those things that happened. I could tell the story. There's a story that would take about ten hours to relate ... all the details. "Like the $77 per hour rehearsal charges and strict union rates they were paid for playing.

"That's it. When anybody says America you can't really say anything apart from either very briefly or tell the whole story 'cos we've answered questions about it for so long now and we've told the lengthy story and we've briefly sketched over it." But as a stunt it was symptomatic of the times. And nowadays there are many, many groups indulging in the same type of promotional buffoonery as Famepushers persuaded Brinsley to lend his name to.

"Yeah, we didn't know too much about how it's gonna work."

The group was not the eye of the furiously whirling tornado of blah "but now the group goes down its own way and everything revolves around it, instead of the other way round.

"You know I find there's a helluva lot of stuff around that's not got much talent. it gets sort of pushed up."

When the band parted company with their last manager, Dave Robinson, Brinsley took over the books. He's getting the knack of dealing with "the people and businessmen," but one feels he'll be glad when he's fully able to hand over the work to someone with a better head for figures, taxes, and so on.

Nine months ago Brinsley decided he'd like to play sax. He started on alto. First of all he was into jazz, then Junior Walker and the funkier players.

Around six months ago he moved on to tenor and that's the instrument he's opted for.

But only for the time being. Everything about the Brinsleys is liable to change. To be settled, to be satisfied, is to be dead. To change, to seek, is to discover and grow and evolve.

That's why Brinsley Schwarz should still be together in ten years' time; still making good, enjoyable, honest music.

|

Billy Rankin

|

Bill Rankin cannot, in all honesty, be called anything less than tubby. It comes of sitting down behind a drum kit all day and all night. The seat of Billy's pants spread wide, his paunch rests happily, his eyes close, head slightly back facing the ceiling, mouth slightly ajar. The beat goes on.

Rankin first met the band one Boxing Day at a place in Tunbridge Wells called the Dalgey Hall. All the local groups would play there at a function promoted by the local agent. The money'd be split among the groups.

Billy had his own band, The Martin James Expression, "in the soul and Motown days" and knew Brinsley and a few of the others in the Tunbridge scene.

Rankin himself was born in New York but has been here since he was seven — 16 years ago.

After the big Tunbridge gig Billy turned pro and went to Germany with his band — "really ripped off. Supposed to get £25 a week and expenses and I got a fiver a week.

Both Billy and Brinsley's groups of the day were based in Munich at the same time. "I got really friendly with them there. I really loved the band, Kippington Lodge, I really dug 'em."

When he came back to Britain, Billy got a gig playing in a beer cellar in London doing "six nights a week playing pop songs and that sort of thing." One day he got a call to ask if he wanted to join Brinsley. He did, "like a shot."

The band he left, he says, was the one that's now called Hackensack, heavy blues trio thing, big fat lead guitarist who's an entertainer, popular in the Northern clubs.

Billy started playing drums because of Z-Cars and Robert Robinson's Points Of View T.V. letters programme. Both had drum-based signature tunes.

First band he was in had a lead guitar, rhythm guitar and drums.

All I had was a snare and a cymbal. We did Shadows instrumentals, things like that.

"That's what amazes me nowadays. Kids nowadays just haven't got so many opportunities to play. And you didn't need any equipment.

"When we lived in Northwood we had a young band living opposite us, just a little band, and the equipment they had – the guy was 14, the lead guitarist had a Les Paul and a 100watt stack and the drummer had a Hayman kit.

"When I started off I had a £5 Broadway snare drum and a little £3 cymbal. But I was doin' gigs. I was out doin' gigs, and every birthday present or Christmas present I'd ask for a bit of drum. 'Til when I was about 13 I eventually had a full drum kit together."

When Billy joined Kippington Lodge, he'd been earning £40 a week, getting free meals and so on at the bier-keller gig. "I left that to go to a £12 a week gig but I was living with my mother (she's English, his father died when he was 11), so it didn't matter.

"I used to give 'em cigarettes cos I had a bit of money in the bank. I used to take 'em round my house to be fed. Cos Nick and Bob were just completely... well, you know.

"But they were so into the music. That's all they lived for. As long as they could get a coupla quid at the weekend for, you know, coupla quid deal, they'd just play all day.

"They wrote some brilliant songs in those days. Which is called starving for your music."

Kippington Lodge was getting "a very depressing thing" when they answered Dave Robinson's ad.

"I really hustled them into it," says Bill.

Brinsley and Rankin met Robinson, Nick and Bob followed. "And that's where Brinsley Schwarz took off... but a little too quickly. But that's life. I've no regrets about that. It was a great eye-opener.

"But unfortunately we were the first people to do it so therefore, I think we got over-slagged 'cos there's been a lot other groups that've been doing it lately. You name it...

"As far as I'm concerned I had a great time in the States. I'd never heard the band play so well" (Billy, in fact, was the one group member singled out as being anything above the average at the time) "and American audiences were fantastic for us compared with English audiences. What resources we had it drew every single thing out."

After it the sympathy started coming in from people, like John Peel. The Press too realised it hadn't been the band's doing "and now we're one of the most respected bands in England. Y'know? We were too young, that's all."

The masterplan, says Billy, was that they should go on the road for two years and then they'd be a good band. ("Which is what's happened now"). Dave Robinson got involved with Steve Warwick (a film cutter, did all the James Bond movies) and Eddie Molton, who had a company called Famepushers.

They also handled Help Yourself. In the end Fame Pushers did not have any money and Brinsley Schwarz ended up paying all the bills.

There were about 11 companies involved; the Schwarz one was the only concern which made money, says Billy.

"We lost about £20,000 out of that from our advances." They've still got some bad business deals left over adds Rankin. "It takes about two years to clean yourself up."

But they're as clean a band as you could wish to hear nowadays. And Billy's a strong, solid drummer with a ear for the right feeling. He plays well with Nick Lowe's bass.

Now that the band's able to ease off the road every so often, they can be selective about gigs. "You can't burn yourself out.

"In a pub or a club it doesn't matter what you look like it's just the music. And that's basically what this band's into. Music. Good music."

|

Ian Gomm

|

The hair that surrounds Ian Gomm's face on all sides is the colour of carrots. It's a face that smiles more often than any other in Brinsley Schwarz. A face that reflects Gomm's easy-going disposition. A face that was the last to join the Brinsleys.

About three years ago Ian saw in the MM an ad ("there's an art to reading them, you know, someone showed me how to sort out the amateurs and the professionals and the heavy business ones, it's quite an art ").

The ad read: "Name Band Requires Songwriter And Guitarist."

"It's funny I just looked at it and thought 'That's Me.'"

Previously Ian had been in a three-piece band with Colin Bass (once a Foundation now in Clancy). When they split the drummer joined the Casuals, Colin joined the Foundations and Ian joined the Schwarz.

At the time Ian was a draughtsman. He quit the day after Brinsleys played the Lyceum.

Gomm started playing guitar in school. "It was like a hobby, A guitar for Christmas present thing which I just kept going. Chuck Berry. It was part of the Ealing scene — you know about that.

"Just after the Rolling Stones, about the same time as Manfred Mann was getting going. About the time the Who started."

Ian says he used to play down the Ealing Jewish Youth Club. "I was the only gentile there. That sort of thing. The Who used to play there. They were called Del Angelo and the Detours then.

"Roger Daltrey used to be the lead guitar, Pete Townsend used to be the rhythm, John Entwistle used to play the bass and trombone in 'Cherry Blossom Time' and Del Angelo used to be the front singer and his brother used to play drums before Keith Moon joined. They used to do the kicks and the brown suit scene."

The group with Bass was the first time Ian reckons he began to feel committed to music. "The whole thing about you've gotta get your group together, write your own stuff and do it like that."

In the three-piece Ian played rhythm and lead. "A style out of favour these days, It wasn't like Jimi Hendrix – really good solo work. It was all we had in the group anyway. In fact I was always in three-pieces 'til I joined this group. Used to be in Tamla three-piece groups that sort of thing. We used to support all the big names down the Kew Boat House. Five pound a night."

He tells a story about the night they supported Pink Floyd there. Syd Barrett had just left the band, he recalls, the place was packed with mods.

"They got booed off, people throwing money at 'em. When we came on people cheered us. I felt really bad. Cos I was enjoying what they were doing cos it was new. They had their light shows and everything."

Does Ian sees Schwarz as a class set of players. "Well, not really. It's just that there is so much crap about at the moment. The record industry reminds me of the film business when all the cinemas started closing down. The market's still there though."

Ian talks about the silly proportions booze boogie has reached. Like the licensee he overheard taking a call from a band who wanted to play his pub. "Send me a tape," the licensee. Some publican acting like an A and R man.

And all the (for want of a better word, says Ian) hippies going into the pubs to listen to the music for free, sitting on the floor, being cool, and then at the height of the evening's trade shuffling to the bar and asking for a glass of water.

"So they started charging on the door and then the whole vibe's gone, It's only good point is that it gave bands somewhere to play but really it's just the same rip-off as before."

And colleges, Ian recalls, the vast "gluts." Eight groups on one bill. We'd all be sitting round in a huge dressing room. All the Jazzers with their hip-flask of gin, Good Habit with their cloaks on ringing bells. By the end of the evening it's just terrible 'cos the audience don't know what's goin' on.

"You know 'Well er Osibisa's on up stairs but I can't really be bovered and, er, so there's Shakin' Stevens, er...' and, you know, Roxy Music are probably on three flights up in some little room.

And as you're playing all these people are walking past looking at their watches to see if there's time for another round. The colleges could've been so good. They still can, like at Leeds where it's done on a much more professional basis."

But whatever the gig Brinsley is a band that'll thrive on it. "You've gotta have a reason for doing it, haven't you? We get the feedback from an audience and vibe on that. We start playing better."

They've had trouble getting the Schwarz mood on record? "Well what we've done before is to play live but it hasn't been as forceful. What we've come to now is to make it something different from performing and not pretend one is like the other which is what we've always done before."

Now, says Ian, with Dave Edmunds at the desk they're after a well produced album "that's not selling out in regards to our live feel but it's still got a 'vibe that we can get on stage. We're not gonna take our live vibe and put it on record. We're gonna make a record that actually stands up as just that."

|

Scanning errors uncorrected...

|

Photos by Barrie Wentzell.

Cover.

|